|

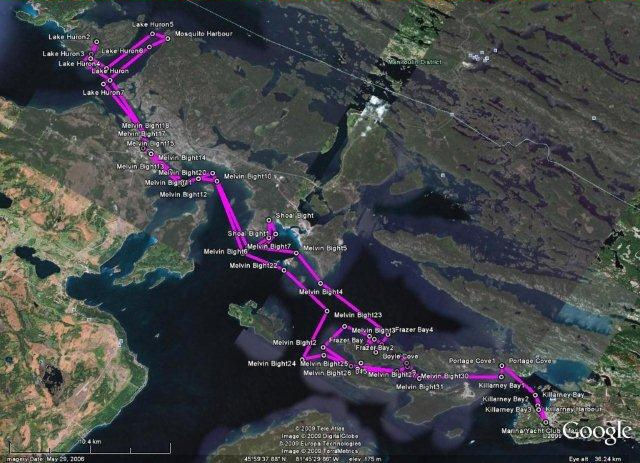

Ted Rosen & Scott Eckert sail W8231 from

...Killarney to Little Current and the North Channel in the Summer of 2009 |

|

|

This trip started one year ago

with my introduction to Wayfarer cruising through Margaret Dye’s

book. In no time at all, I experienced two-footitis, and replaced

the CL14 which I had been sailing for 10 years in Toronto’s Outer

Harbour with W8231. The learning curve was steep, including

progressively longer solo ventures into Lake Ontario and along the

shoreline, gaining confidence in the Wayfarer's ability to handle a

wide variety of cruising and racing conditions. I also learned more

about the Wayfarer through replacing fittings and refinishing seats and

centerboard. This included an incident when a shroud bolt sheared in

modest winds requiring on the water repairs and judicious return to the

Outer Harbour Centerboard Club, from which I sail.

Through the Canadian and US Wayfarer web sites and cruise logs, plus numerous questions to Uncle Al, all of the components needed to plan and conduct my first week-long cruise were assembled. From the cruise logs, I gathered that most cruises were relatively relaxed sailing with the occasional day of exhilaration. Little did I know that the inverse would be true for our trip? During the 2009 sailing season I did a number of solo shakedown cruises, but none longer than an overnight. They provided valuable lessons in navigation, living and cooking on board, and anchoring - all relatively new to me, on the water. I did fall back on almost 40 years of mountaineering and backpacking low impact camping experience to guide many of our plans. Thanks to the many sources of information about local cruising areas, I settled on the Georgian Bay, with the intention of doing a solo cruise along the route described in the 2001 Georgian Bay cruise report. The North Channel is reputed to be a most spectacular sailing area, and a natural destination from a Toronto base. Fortunately for me, when I described my plan to my sailboat racing partner Scott, he immediately asked if I would be interested in being joined by an experienced crew, namely himself. This was a no brainer, and we agreed to finalize plans for the trip when I had returned from competing in the Ironman triathlon in Lake Placid, New York, at the end of July. I intended this cruise - especially with an excellent crew - to be a relaxing break from triathlon training. As it turned out, the week of

sailing was only possible with Scott on board, and I could not think of

a better partner to sail with. Scott has been sailing as long as

I have, and had cruised with his brother on a Wayfarer in the Yukon, as

well as being familiar with the Georgian Bay area as a youngster.

Our years of racing together allowed us to work as a team, especially

when each days conditions inevitably became challenging.

Although I had keelboat cruising experience, I had never completed more than an overnight trip in my own sailboat. Nor had I loaded a boat on a trailer, or towed it. My anchoring experience and sailing in much over 12-knot winds was limited. The trip was meant to get the process started, and expose me to all the basic cruising tasks, in hopes of many more trips in the future. My intended relaxing holiday though, morphed into a constant state of anxiety while in motion, offset by temporary states of rest when anchored and secure.  departure & mast support Our trip started on my return to Toronto, and the confirming phone call that Scott was available and ready for the planned trip. Scott was to organize the food (I later found out he had worked as a summer camp cook for geological survey teams) and I was to look after all else. We met at the OHCC to load the Wayfarer on my boat trailer, and assess any further needs. I had completely rewired the trailer earlier in the spring, yet one of the rear light lenses had been broken in storage and needed replacement, (lesson learned: in the future I would opt for a lighting board rather than conventional trailer lighting) and we decided that an additional mast support was needed at the bow. Scott being a highly skilled furniture designer and wood worker proceeded to take a few measurements and produce a custom support in no time. Thursday was spent assembling the food and all necessary cruising items with the agreement to make an early start Friday morning, in hopes of missing the August long weekend traffic. Friday,

July 31 Toronto to Killarney to Covered Portage Cove

departing from the OHCC I picked Scott up at his house and we pared down the food piled on his dining room table to a reasonable quantity. It seems that Scott shopped as if he were feeding a geological survey crew. Loading the food and his personal gear in the car, we proceeded to the Outer Harbour Centreboard Club to pick up the Wayfarer on the trailer and head north. My first trailer experience was in now to be in Toronto long weekend commuter highway traffic. I needed to remind myself constantly that I was towing something bigger than my car. My anxiety was unnecessary, and all went smoothly. After about 30 minutes we pulled into a service area to check the tires and confirm bearings were not hot, as well as pick up some coffee. The next five hours of driving went quickly as Scott told story after story of his past adventures.  launching in Killarney We arrived in Killarney before

5pm. As reported in other cruise logs, the main street ends at a boat

ramp. (The adjacent fish shop charges $7.50 each for put-in and

take-out.) Parking for vehicle and trailer are conveniently

located behind the church about one block away, with a daily “donation”

of $5. By Toronto standards we were ahead of the game. The

weather was clear, so we loaded the Wayfarer, stored the vehicle and

cast off. Although the wind was not strong, it was on our nose

for the length of Killarney channel, and we were continuously tacking

as we made our way out to Killarney Bay, to the amusement of local

residents lounging on shore. I had both paper charts and a

GPS. The rapid departure did not give me the opportunity to plan

a route, but fortunately we identified an anchorage which turned out to

be Covered Portage Cove, a very popular spot for the night. Due

to our shallow draft, we were able to access a quieter portion of the

bay, to allow both good anchorage as well as access to shore as needed.

The anchors set well in the mud and weed bottom. Generally the two

anchors I carried, a 5-lb Bruce, and a larger guardian anchor

complemented each other and held well. I am constantly amazed how

the Wayfarer swings at anchor, which is quite unsettling without the

boom tent, but virtually unnoticeable with the tent up and the view of

surroundings blocked.

cooking set-up  boom crutch  Scott relaxing on board I had researched and practiced

cooking on the Wayfarer, and had purchased a Jetboil camping

stove. It had the advantage of being very efficient due to a heat

exchanger system on the pot, use of a gas cylinder avoiding liquid fuel

spills, and had and add-on suspension system, allowing the entire

cooking system to be suspended from the boom. This was an

inverted gimballed arrangement which worked perfectly, adjusting to any

motion of the Wayfarer with no hazard of hot pots or lit stove falling

over. With dinner complete, we set the Wayfarer up for sleeping with

Thermarest pads, sleeping bags and enclosed the Wayfarer with a boom

tent obtained from Hans Gottschling. Scott was later to say that

it was amazing that the boom tent was both easy to set up and worked so

well. Sleeping in the confined quarters was a learning

experience. Scott initially tried sleeping with his head forward, ala

Frank Dye, but that lasted only one night. It took a few days of

experimentation to determine the ergonomics of comfortable sleep.

August

1. Covered Portage Cove to Frazer Bay

We got a late start, following

breakfast and a visit to shore. Sailing west through the

Lansdowne Channel, we were continuously tacking into the increasingly

stronger winds. As we rounded Badgeley Point, Frazer Bay was filled

with whitecaps and waves. The 15-knot and higher wind forecast

was to plague us for the next week. It seems that this year has

had much higher winds than was typical. The conditions were

certainly more than our comfort level allowed, and we had previously

agreed that as a first venture into multi-day cruising, we would sail

conservatively. We rounded the point and tucked into the first

inlet to assess our next steps. A careful look at the chart

showed a better protected Boyle Cove further east, and we proceeded to

this location to anchor for the day. The afternoon was spent

swimming, eating lunch, and taking it easy. Swimming from the boat gave

the opportunity to practice using the main sheet as a foot loop to get

back in the Wayfarer, should that ever be needed in a man overboard

circumstance. It rained later in the afternoon and more heavily

during the night. The boom tent worked well. Through the entire

cruise, very little water entered the Wayfarer, all of which found its

way to the bailer scuppers, and could easily be sponged out.

August

2 Frazer Bay to Stoney Point

View from Stoney Point We were up at 6am, as we found

was both natural and needed due to the daily wind patterns. The

forecast was for 20-kt winds gusting to 40kts from the west, so we

needed to sail early to limit our exposure to the higher wind and seas.

Under the forecast conditions, we may have been wiser to sail north or

south, rather than into the wind. Our objective was Little Current. The

mailsail was reefed by 10:30 am, and once again we sought refuge in a

bay protected by Stoney Point identified on the chart as Shoal

Bight. Once again we found a soft bottom for anchoring, and in

addition tied the stern to shore for ease of access. Following

lunch we hiked across Stoney Point to the North Channel, allowing us to

confirm that the sailing conditions were well beyond our comfort level.

Keelboats were motoring into the wind. Scott pointed out poison

ivy on our walk, and whether it was here or from another anchorage, I

developed a mild case of this affliction. Caution is advised.

Each day’s high winds diminished to calm at nights, and at various

times mosquitoes became an annoyance. In anticipation of this, I

had brought a mountaineering bivy sack, which although confining kept

the bugs out. There must be a better solution using mosquito

netting, but I have not found it yet.

August

3 Stoney Point to Rouse Island

Little Current bridge Red sun in the morning.

Hmmm. We dressed for the worst. We intended to be at the Little

Current Bridge crossing this day, somewhat later than the original

schedule. Foregoing breakfast (and to Scott’s dismay, coffee) we

were sailing before 7 am. Once again the winds started to

increase with some rain, but as we approached the bay near Strawberry

Island, the winds became shifty and variable. At times I

felt I was heading away from our destination, and we clearly were not

going to meet the 9 am bridge opening, despite a valiant rowing effort

on Scott’s part with the oars. We chose to anchor near the bridge

to wait for the 10 am opening, rather than wear ourselves out

manoeuvring around the wind shifts and other boats queuing up. As the

appointed hour approached, we retrieved the anchor and reached back and

forth near the channel marker, waiting for signs of the bridge

moving. In retrospect it was much like the start of a race, and

that is something that Scott and I were comfortable with. Most

race starts are not constrained by bridge abutments, larger boats

motoring across the line, and the prospect of a massive bridge crushing

your mast. Once through the gauntlet, we tied up at the public

dock while Scott took the opportunity to phone home and pick up coffee

and breakfast. It was a cool, cloudy day, threatening rain, yet

we had achieved our objective of passing the Little Current Bridge, and

felt very good about that. The facilities at Little Current had

been vastly improved since 2001. Finger docks were filled with a

large variety of sailing and motor yachts and clean washroom facilities

are available. Our 16-foot dinghy felt particularly small in this

company. There is no charge for day use, but overnight charges

were near $2 per foot. I thought about the 40’ Hunter adjacent to me

paying $80 per night, and remembered why I was sailing a Wayfarer.

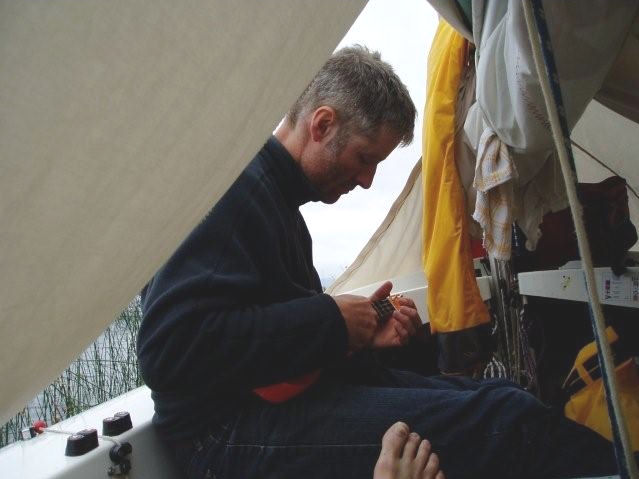

Scott playing Emergency Ukelele  Rouse Island anchorage With breakfast and phone calls

complete, it was still early in the day, so we cast off with the

intention of sailing as far west as conditions would allow. As we

passed the Waubuno Channel the winds and waves were piping up again,

and with reefed mainsail, we entered the anchorage between East and

West Rouse Island. We were now being blown to the northern end of

the bay, at great speed. In an attempt to stabilize our situation, we

dropped anchor, but the anchor dragged, and we found ourselves stopped

by reeds at the shallow North end with no harm done. Thankfully,

the bay was not filled with shallow rocks. Out came the oars and

we fought our way to the west side of the bay, where more protection

was available, tying onto shore. Once again our sailing day was

shortened by wind and waves. Lunch was followed by a short walk,

dinner and a quiet evening. Scott brought out his emergency ukulele. This was a

bright orange colour ukulele intended for those quiet times when

Scott’s urge to create music could not be restrained.

The dinner/tent set-up ritual

had now become quite efficient, almost effortless. As it became

dark, the strong winds of the day abated, and we were faced with ...

mosquitoes. After an hour, the annoying insects became too much

and we pulled back the tent to row further out into the now calm

bay. It did not really help reduce the mosquito density, but we

anchored and pretended to sleep. Through the night there was a

thunder storm, and I reflected on the discussion

about lightning in the Wayfarer Institute of Technology web

site. Counting the number of seconds between lightning flash and

thunder, indicated that the storm was sufficiently far away as to not

be an immediate concern. Scott was not so convinced.

Near 5 am, the wind did pick

up, and it appears that it clocked 360°, allowing the anchor rope

to wrap around the rode and dislodge the anchor. Scott said he

could see the panorama of our bay through the screened stern boom tent

window just prior to our being blown into the reeds once again.

So much for a good night’s sleep, and confidence-building

anchorages. We rowed back to our “dock” and accepted that the day

would soon begin.

August

4 Rouse Island to Mosquito Harbour

Throughout the cruise, we could

easily receive marine weather broadcasts on the handheld marine

transceiver I had brought. At one point I had explained to Scott

the various protocols for transmitting, should we need to. We had heard

reports of a keelboat Mayday call. The forecast for the day was

20-25 kt winds and 1-2 meter waves. We no longer felt we could

progress westward, and resigned ourselves to an idle day, when one of

the keelboat sailors also anchored in the bay rowed his inflatable

tender over to chat. He suggested Mosquito Harbour at the north

end of the Waubuno Channel was a more pleasant location. Within

20 minutes we were sailing for this anchorage, through increasing wind,

but at least we were moving. The bay was west facing and we were

blown into it but found a more protected niche on the north

shore. The holding was good for our anchor although large

submerged logs had the potential for fouling the anchor, and we spent

some time setting the anchors to allow easy retrieval. By the

time we had tied off the stern, whitecaps and waves were invading our

bay, but we were reasonably protected. Another short day, with

swimming and some short hikes on the trail and dirt roads which

appeared as if a developer had ambitions for the adjacent land.

Walking to the exposed open water north of Northwest Point confirmed

our decision to stay put: high winds and whitecaps filled the

view. We were joined by two larger motor launches, which with all

their power and manoeuvrability chose to anchor for the night.

Towards the end of a quiet afternoon the owner of one of the boats

rowed his inflatable over to us to chat. Asking whether we were

daysailing and in need of accommodation for the night, we assured him

that we were all set for the evening. He referred to sailboats as

“stick boats” and we understood that to mean that many of the keelboats

spend the greater part of their time motoring in the North Channel.

Having no motor, we sailed, rowed or anchored. We did appreciate

his concern for our well being. Oddly, we were not bothered by

mosquitoes in Mosquito Harbour, and the incoming high pressure system

brought cool dry weather, allowing one of the most restful nights of

the cruise.

August

5 Mosquito Harbour to Covered Portage Cove

return from Little Current - Ted at helm We had passed our cruise

midpoint and it was time to start working our way back to

Killarney. With strong winds again forecast for the day, we were

up at 6 am and sailing 30 minutes later. Waubuno Channel was

manageable, but rejoining the main bay raised the question, “Is it time

to reef?” I had learned that if you ask the question, it is likely

already too late, and Scott at this point had developed good skill at

reefing the main. We had roller furling on the jib, but reducing

the headsail did not work well. Now with the wind astern, I aimed

to maintain a broad reach to reduce accidental gybe potential, and we

sailed at 5-6 kt boat speed back to Little Current. The unexpected

appearance of a huge cruise ship bound for Little Current further added

to the increasing challenge of sailing. Fortunately they were

clear ahead by the time we were in the narrower channel. Rounding up to

the finger docks had its moments, but a second try, aided by a few

helpful sailors on the dock, allowed us to tie off while waiting for

the next bridge opening. Scott was off once again for phone

calls, coffee and breakfast. The current in this channel

apparently changes both speed and direction, and on this day it seemed

rather strong flowing in an easterly direction, pushing us towards the

bridge. Unsure of how long we would need to travel the distance

from the dock to the bridge, we cast off 15 minutes before the hour,

resulting in about 20 minutes of tacking back and forth in the channel

and attempting to avoid the other boats queuing up for the

morning. The wind required an angular approach to the bridge, and

once again our many race starts allowed us to cross the line without

being called over early, or being crushed by either a larger boat or

swinging bridge. Fortunately there was no general recall.

Typically, we would plan to

take each section of the day separately, evaluating the safety of

continuing and constantly on watch for protected shelter. The

west wind was likely as strong as we had experienced in previous days,

but now we were sailing on a broad reach. The apparent wind was much

less, and we were no longer pounding into large swells. In fact

we were riding the swells, at upwards of 6 knots, and at times

surfing. We seemed to be sailing at least as fast as the larger

boats surrounding us. I marvelled at the stability of the Wayfarer in

all of the rough conditions we had experienced and it gave great

confidence to be out in the larger open water. We had now been

sailing continuously for 6 days – more continuous sailing than I had

ever previously done. We were moving at great speed, and rather

than risk a change in weather by stopping for lunch, we headed back to

Badgeley Point. What had taken us 2 days to sail was now

completed in 2 hours. We considered the alternative route south of

Badgeley Island, but once again winds and wave had become intimidating

by noon, and we opted for the more protected Lansdowne Channel. Rather

than immediately returning to Covered Portage Cove, we poked our nose

into a number of smaller bays along the way. The fluky winds, and

rock-studded bay thwarted our efforts to anchor resulting in our

re-entry to the Lansdowne channel under jib alone. This was

relatively new to me, and the jib pulled us along at 5 knots, with no

concern for accidental gybes. All seemed good, until we found

ourselves approaching Covered Portage Cove with the need to sail

upwind. A previous experience in these winds suggested that the

jib would not get us where we needed to go. We attempted rowing, but

the wind was too strong. We unfurled the jib and sailed into open water

to raise the main. Without the ability to sit head to wind,

raising the main, even as reefed, failed and the bolt rope escaped from

the mast track, followed by the halyard swage jamming in the mast

sheave. So much for a relaxing sail.

This was one of our longest

days on the water and we later decided that our conservative earlier

days were a good choice. In spite of the confusion, it was a

credit to our sailing relationship that we could assess what needed to

be done next, talk it out, and solve the problem. We found a

quiet recess in the cove to bring the Wayfarer to shore, secure it, and

lower the mast while on the water, to allow access to the mast head.

Our little drama was somewhat comically conducted adjacent to a couple

of huge cruisers, complete with multiple generations of grandchildren

through grandparents, all obliviously acting as if they were on

holiday. With the mast lowered, I worked my way over the slippery

rocks to the mast end, now some distance from the stern and with a lot

of manipulation the swage was freed, and the halyard returned to its

proper position. Gaining experience raising and lowering a mast

on the water is useful, but not recommended for a multi-day

cruise. Needless to say, the forestay cotter pin ring liberated

itself, and fortunately I had multiple bits and pieces in a repair box

to allow replacement. Carrying a leatherman tool was really

useful. With the mast up again, raising the main allowed beating into

the bay to our quiet cove with only a bit of pinching to avoid the

exposed rocks and anchored boats. A big sigh of relief was given

once the anchors were set and holding. It was time to get out the

“emergency ukulele” and offer thanks to the sea cruising gods for

another safe anchorage. (Sea gods appear to like bluegrass music)

Covered Portage moon Our cruise was close to

complete. From Covered Portage Cove it was even possible to

access the cell phone network and send text messages home to say all

was well, and we would be returning Thursday evening.

August

6 Covered Portage Cove to Killarney and Toronto

We awoke at 6 am on the final

morning, and were sailing shortly afterwards, navigating around Sheep

Island to the relatively obscure channel inlet to Killarney. I

had relied extensively on a GPS with marine charting for our

navigation, backed up by paper charts. Throughout the cruise I

found it quite challenging to both focus on the helming and sail

management, and know where on the paper chart we were. The GPS

solved this admirably, and served as a constant reminder that should

the GPS fail, a high level of chart reading skills would be needed.

return to Killarney Harbour  unpacking and preparing to haul out Our last morning was the most

relaxing sailing of the week, with relatively light winds. We were back

to reaching up Killarney channel and a quick rounding up to miss

the coast guard rescue vessel filling the bay at the boat ramp got us

to the unloading dock unscathed. Our first priority was to have a real

breakfast, and coffee, followed by retrieving the car and trailer and

packing for the drive home.

We were really pleased to have

successfully completed our planned cruise, adapting to the strong wind

and wave conditions in a safe manner, in a boat which was smaller than

any we had seen in the week.

Although a week of relaxing sailing full days was not realized, our first “real” cruising experience exposed us to a wide variety of sailing and challenged our ability to sail safely in conditions approaching the limits of our comfort level. Spending a continuous week sailing gave rise to thoughts of how our future cruises might be different. Sailing in this area requires constant vigilance regarding water depth and submerged rocks. We encountered the occasional unexpected shallows, frequently hidden by rough water. During the week, we had decided to leave the rear seats in place, although many cruisers choose to remove them. I found the sailing more comfortable with this seating arrangement, and the storage capacity of the Wayfarer did not cause crowding. We were curious whether any modifications had been considered for reducing the mainsail height, and raising the goose neck, giving more headroom and visibility when sailing upwind especially in higher wind conditions. Scott used a conventional racing life jacket, but I found the inflating life vest quite comfortable. The rings on the vest, intended for a safety line when solo sailing, served well to secure the wrist loop of the handheld GPS, which then could be tucked in my jacket pocket until needed. The GPS was then readily available for quick checks, but not otherwise in the way. The last item regarding boat set-up was another reminder of the importance of checking equipment. At the end of the cruise, I lightly tugged on the forward hiking strap and the securing line broke due to abrasion during the trip. This could have been quite disastrous on the number of occasions when Scott hiked out during a gust. Keeping an eye on such fittings and fixtures at the end of each day is a worthwhile task. As a novice cruiser and

Wayfarer owner, I also learned that a sailboat takes a beating during

road travel and a week of cruising. Awareness of the potential of

damage is an important component of damage control, and inevitably

post-cruise cleanup and (minor) repair are needed. The hull did

receive a minor coating of road asphalt from highway maintenance

patches, and I would explore purchase of an undercover for future

trailering. The positive side of this was that the day following

our return, I turned the Wayfarer on its side, and swabbed the hull

with solvent, cleaning debris, inspecting and patching minor damage and

loose keel band screws. Minor touch-up of wooden seats,

centerboard and rudder were also needed, preparing for the remainder of

the sailing season.

This cruise would not have been as successful without the information gained from the Wayfarer cruise logs, helpful suggestions from Uncle Al and his many worldwide Wayfarer contacts, and Scott’s participation. Thanks to all. Ted Rosen W8231 |