|

Spree

Lady's Irish Cruise 2011

Day 4, Part 1:

Just another day at the office, really. Our "office" is Ralph

Roberts' custom cruising Wayfarer World. We attend to the

one-and-a-half-hour morning ritual of converting Spree Lady

from her sleep mode to sailing mode. There are the usual overcast

skies, possible drizzles, SW winds F4-F6. Once underway the salty

spray of the Celtic Sea jets up my sleeves and nose, down my neck and

stings my eyes. And occasionally, just to keep the crew alert,

there are the bigger bully waves that shoulder their way over the deck

and into the boat. I'm seated at my usual station on the thwart

facing forward, ready to adjust the genoa sheets or reef the main as

the captain decrees. All's well in our wet little world as we

head for Kinsale, just one of the 14 ports we were to visit enroute to

our destination of Dublin.

Spree Lady is scampering along nicely in spite of the secondary waves reflecting back through the primary, Atlantic-born waves destined to hurl themselves against the Irish headlands. Suddenly, I hear Ralph call out unexpectedly and quickly turn to see what's different. Ralph is, indeed, (in the technical sense) still at the helm, tiller extension very much in hand. There is, however, one aspect of this scene that is utterly shocking - Ralph is not in the boat, he's in the water! He remains attached to the boat by nothing more than the small piece of rubber which connects tiller and extension! In that split second between panic and adrenaline-fueled action, a terrifying scenario flashes through my mind - an entirely different fate which, even now, I am reluctant to contemplate. (To be continued) Prologue: But I've already gotten ahead of myself. Properly told, the log of our 200-mile cruise along the southern Irish coast began the year before when, after I had bought some used sails from Ralph, he cast an offer my way which I was eventually unable to refuse. As I was saying good-bye, he mentioned that he was considering an Irish cruise the following year and would I be interested in crewing? I had bought an old Wayfarer two years earlier and sailed it perhaps 15 times. In terms of dinghy sailing experience I considered myself a complete novice. On the other hand, I had done my homework; I had read numerous accounts of dinghy cruising including Ralph's. This could be a chance of a lifetime to gain actual experience from a veteran cruiser. I finally accepted his offer (not without numerous negotiations on the home front) and preparations were begun in earnest. I was later to appreciate that armchair sailing is a whole lot warmer, drier, and has inherently more options than the real thing. Even in the most treacherous predicaments, I can always put a paragraph on pause while I fetch another beer from the fridge. Out there, on the water, pursued by endless legions of white horses, the only thing I managed to pause was my need to "spend a penny" as Margaret Dye so quaintly phrases it. Indeed, often unable to "spend", my piggy bank was regularly filled to capacity…and then some. And this is just the pennies, which is to say nothing of the "pounds". So, in June 2011, Ralph

met me at the Dublin Airport literally within seconds of my clearing

customs. We headed straight away for Monica Schaefer's residence.

Monica is Ralph's Irish contact and a most gracious hostess. Both Ralph

and I were quite exhausted from our travels and that night, according

to Monica, we had a snoring contest; apparently it was a draw as

neither woke the other.

Next morning, after attending a boat jumble in Dun Laoghaire (note: there is absolutely no relationship between the spelling of an Irish place name and its pronunciation - Laoghaire being pronounced Leery) - we set out for the B&B we had reserved near Cork. We managed to arrive past food serving time at the local pub so dinner consisted of a pint of Murphy's. No matter. The jet lag persisted like a cheap whiskey hangover; food easily took second place to the need for sleep. Day 1: A full

Irish breakfast including fried haddock more than makes up for the

missed dinner. After shifting the cargo in the hold of Ralph's Citroen,

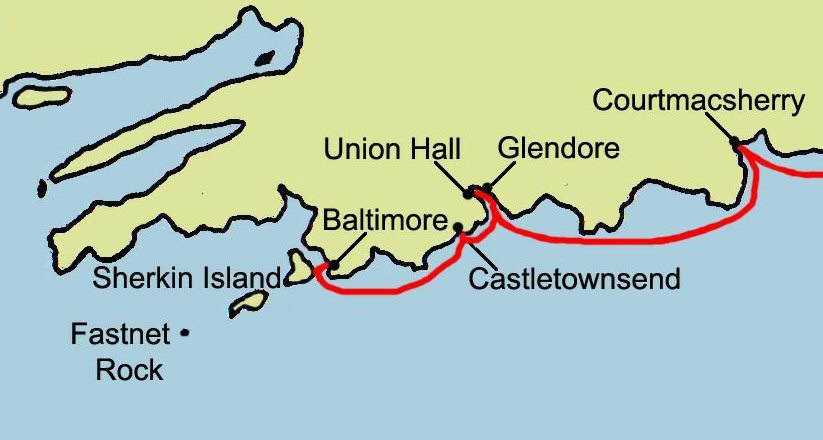

we are joined by Philip Murphy and soon get underway for Baltimore

which is to be our point of departure. Located on the extreme southwest

shore of Ireland, Baltimore lies about 10 miles from Fastnet Rock,

famously associated with the 1979 race of the same name in which 15

perished in a vicious F10 storm. We will be sailing in waters deserving

of our utmost respect.

We finally arrive and begin the preparations for launching. At this point I should interject that most launch sites in Ireland consist of nothing more than old rock or concrete slipways - not at all like the California versions I'm accustomed to with well engineered anti-slip patterns laid into the ramp and, of course, the usual pontoon/floating dock to which one ties up while loading or unloading. No, in Ireland you're pretty much on your own. With tidal ranges of up to 4 meters and significant surges, it goes without saying that to launch your boat in Ireland, you must launch yourself as well. Ralph has done this hundreds of times and all goes well until an inept line handler (me) allows the boat to become angled to the intractable surge bent on shoving the boat broadside. I manage to prevent the bow from charging back onto the slipway but cannot control the stern which slews into the rock wall bordering the slipway. I am powerless to alter the inevitable course of events as the solid iroko outboard motor mount smacks soundly into the wall and splits. Strangely, Ralph does not demote me from Crew to dunnage or revoke my life-jacket-wearing privileges. The profile of my learning curve has just taken on that of the stock market, October 1929. In an instant my Bright Monday has morphed into Black Friday. Ralph makes an amazing emotional recovery and effects ingenious repairs with bits and tools from Canister 3, Bin 5, Boxes 5 & 7. As a librarian I am acutely aware of the need for precise organization. Ralph's stowage system easily rivals the shelving system of Melville Dewey. Within a short time, he's got drill, saw, scrap wood, fasteners and proceeds with a fine repair. The cruise will continue after all. We bid farewell to Philip who will drive the car and trailer back to Cork for safe keeping.   We push off into a F4

on a close reach bound for Sherkin Island. Coming into what will

be the first tack I hear Ralph say "Plate, please!" Plate??? No

response from the crew. Ralph immediately leans forward and pulls

the centerboard into proper position. Tack saved; ego bruised.

I'm having serious qualms about ever being of any help to Ralph.

We did make it to Sherkin Island where I was introduced to the intricacies of Ralph's stowage system - a marvel of organization and efficiency - developed over decades of dinghy cruising. We (mainly Ralph) converted Spree Lady to sleep mode and celebrated our short first leg with a well deserved pint and meal at the pub overlooking the bay. Day 2: After

breakfast we ready the boat for sailing. It's the reverse of everything

that was accomplished the previous evening. Even if the twice-daily

drill is familiar, it's still an hour and a half of meticulous stowage

and attention paid to lashing everything into its proper place.

Sisyphus has nothing on this dinghy cruiser!

We cast off to a beautiful F3 breeze bound for Dublin - with as many or few stops as we fancy or weather dictates. Our first port of call is Castletownsend, intended only as an opportunity to stretch our legs and enjoy a pint. The landing is tricky as there's no pontoon or guest dock. Indeed, there's no dock at all - just an old stone slipway. Ralph comes in for a perfect landing and I step off. He decides to temporarily tie up against the wall adjacent to the slipway. With painter in hand I'm charged with getting quickly up to the top of the ramp and over to the wall while simultaneously controlling the bow. I am not fast enough and do not anticipate how heavy Spree Lady is when fully laden. My desperate tug on the painter is too little, too late. The protective metal band on the stem just grazes the stone steps and is damaged. In one moment I'm

entranced by having sailed on the Celtic Sea in a dinghy to one of the

most enchanting harbors on the south coast and, in the next, I'm filled

with self-condemnation and doubt. Had there been a plank on board,

Ralph would have been quite justified in ordering me to walk it. The

resulting capsize would have delayed getting that pint of Guinness so

better to just make repairs.

We cast off again bound

for Glandore. It's glorious ocean sailing (F4 - F6) and worth

every one of the thousands of miles I've traveled to experience

it. This is the kind of sailing that draws Wayfarer sailors to

the open ocean. Ralph is completely in his element; I am unsure,

a little nervous, and totally exhilarated. At times we are planing at

over 10 kts - something I would have thought impossible for a heavy

cruising dinghy.

As is common in the smaller harbors there is no guest dock at Unionhall which is on the opposite side of the bay to Glandore. Our only option is to tie to a vintage pontoon used to store the local rowing boats. Tides here, unlike those of western North America, must be reckoned with. As Ralph notes from his cruising guide, Unionhall is a drying harbor. The photo in the guide clearly shows that, at low tide, neither the pontoon nor any of the boats tied to it are floating. A quick calculation tells us that we need to re-position the boat; otherwise Spree Lady could settle onto unseen rocks and seriously damage her bottom. We did finally take the ground during the night but without consequences. Day 3: Next

morning we are visited by a most engaging constable. At first I thought

we might be fined for using the pontoon. But he's come by to inquire as

to our passage and to assure us that we had been personally looked

after in the wee hours. With expert local knowledge, he warns us of

various hazards that are not visible at high water. We are also told

that to have tried to wade ashore at low tide through the mud could

have been very messy indeed. Doing so was, in fact, fatal to a ship's

boy sent ashore centuries ago. The ooze was (and is) so enveloping that

he was unable to reach the shore before being inextricably sucked down

and suffocated.

Time and tide wait for no man. And so it is for us. Rather, it is we who must wait for the tide. Within half an hour, we have sufficient water to press on to Courtmacsherry. We are carried by strong winds for most of the day and again find ourselves planing under full main and genoa. It is a struggle but when we finally reach the pontoon dock we are surprised and disappointed to discover that all available space is occupied by two large yachts and the local offshore RNLI lifeboat. There emerge two options: 1) shoehorn ourselves into the cluster of local dinghies at one end or 2) tie up to the dock opposite the large yachts. The downside to this is that there is an enormous accumulation of thick, green algae through which we must drag Spree Lady in order to secure a berth for the evening. After serious hauling and shoving, Spree Lady is at last resting in and on the algae much like an elongated entree served on a huge bed of wilted lettuce. Finally, fed and tucked

in for the evening, I'm more than ready for a

quiet night's sleep. Although Spree Lady is resting

silently on her green algal quilt, the large gangway leading down to

the pontoon creaks and groans intermittently for the next 6 hours on a

falling tide. The sounds remind me of Hollywood movies in which

submarines are taken to their "crush depth". My dreams are

sprinkled with scenes of seams springing leaks which (perhaps not so

oddly) coincide with my need to "spend a penny".

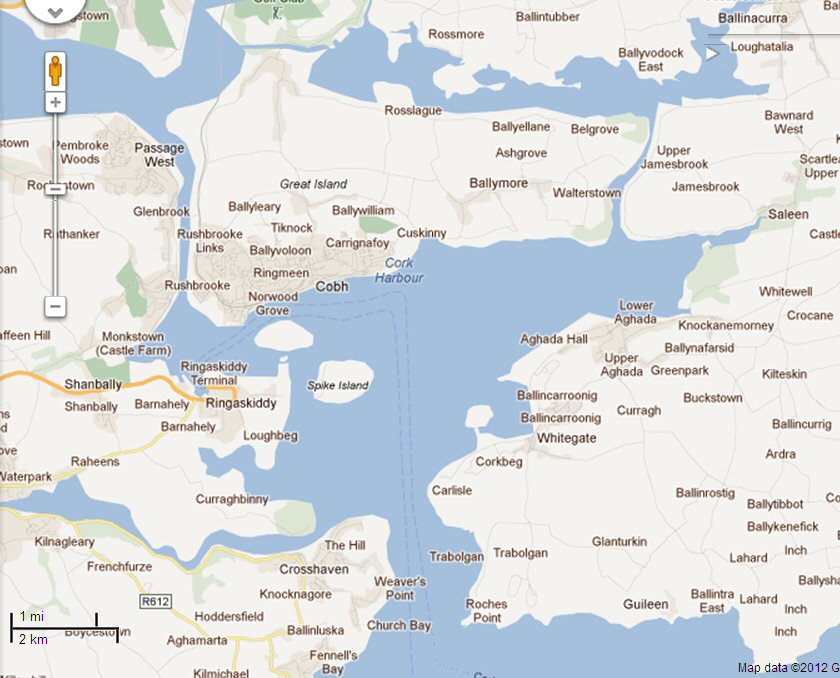

Day 4, Part 2: As I make my way ashore the next morning, I have to ascend the gangway that has been so noisome all night. Due to the extremely large tidal range here, it becomes quite obvious that the gradient has increased dramatically and my legs make it quickly known that they're not entirely pleased. It occurs to me that as the earth's climate warms and oceans rise, the gangways of the world at low tide will rest at much lower angles. Perhaps there is something to be said for global warming after all.  Today our destination is the picturesque city and harbor of Kinsale, well known for its excellent restaurants which offer some of the finest seafood in all of Ireland. It is with clear skies and gastronomic anticipation that we set sail that morning oblivious to the events that will unfold on our journey this day.  (The following is the continuation alluded to at the beginning of this narrative) As already recounted, we were having another day of very lively sailing. My ability to take in a proper reef was constantly being tested. With the winds at F4 - F6, we set course for Kinsale. It wasn't very long after departing that we encountered the conditions described earlier off the coast at Seven Heads. Moments before Ralph deserted his post, the waves seemed erratic and confused. With the winds from the SW we were reaching on starboard tack, Ralph compensating for the rolling as always by simply leaning inward from his seat on the side deck. Whether it was a rogue wave, a rogue trough, a momentary lull in the wind or some combination, we'll never know. All we do know is that the roll to weather was so pronounced and so prolonged that Ralph was unable to lean in long enough to prevent becoming unbalanced and tipped overboard. My first panicked

response is to cast off the main halyard in order to

reduce forward drive. I quickly move to the stern to grab

Ralph. My first two attempts to pull him into the boat are

thwarted by his buoyancy aid catching on the outside lip of the

gunwhale. On the third (and thankfully successful) attempt I

maneuver him first away from the gunwhale and then up and onto the

boat. My great fear at the time was that I would lose my own

footing and balance. Fortunately I didn't.

To reverse our course would mean beating back into contrary winds, so Ralph decides to continue on toward Kinsale. After recovering some of my composure, Ralph and I swap duties and I take over the helm for what seems like forever. We are under double-reefed main and reefed genoa and carry on toward Old Head of Kinsale, finally getting into its lee. The winds abate somewhat but soon we find ourselves planing into the harbor under full main. The concentration required in these winds with 3-foot swells surfing the boat at double digit speeds is unbelievable. Ralph takes over the helm as we enter the harbor proper. It's an enormous effort to pass the helm as my hand is now rigor-mortised onto the tiller extension. Our eventful passage is

celebrated by hot showers and a superb fish

dinner. We are both grateful and relieved that nothing more

serious happened. Of course, there are the near endless

permutations of "what if", "could have", "should have" but in the end,

things are always as they are and no amount of speculation has the

slightest relevance. We will continue the cruise within that same

unknowable space/time continuum in which our lives unfold moment by

moment. I think it's called Life.

Day 6: After

recovering for an additional day in Kinsale,

we perform

our morning sleep-to-cruise ritual and are underway in spite of light

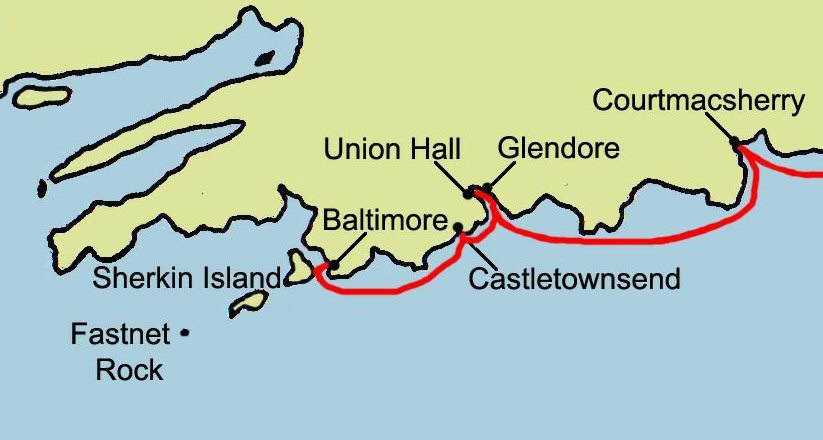

rain and winds. Today we're heading for Cork and, as we slowly

pass Fort Charles built the 1670s, the wind begins to freshen and

it's not long before we need to reef the main and partially furl the

genoa. One of the tricks I learn from Ralph that day is to keep

some headsail while running as it acts as a big telltale and can be

useful in forestalling accidental jibes.

After nearly two hours, we round Roberts Head looking for some protection from the F6 winds and find a little. The captain offers to let me helm on our way to Cork. The wind gets up even more and the first reef is tied back in. Even so we are still surfing north in anticipation of finding shelter from the wind as we approach the lee of Crosshaven Hill. We notice that there are full-sized yachts racing off to our starboard - many single- or double-reefed. The winds at this point (F6-F7) are challenging but manageable. We pass Ramshead and begin to enter the harbor proper fully expecting the winds to abate. They do not. Rather, we find that they are actually increasing and gusting more frequently. These conditions are far beyond my experience and ability to manage and prudently Ralph takes the helm. There are two choices: 1) to make for Crosshaven which would require beating directly into these ill-tempered winds or, 2) to bear off on a close reach toward East Ferry in the hope of finding eventual protection in the lee of Great Island. The second option,

although a longer distance, seems less

confrontational and promises a quieter anchorage. Option 2 it

is. As we bear off slightly to starboard and set course, it soon

becomes apparent that the winds are growing even more vicious.

Short-fetch chop is building at an alarming rate and the now more

frequent gusts threaten to overwhelm us in spite of our reduced

sail. At times the spray feels like Neptune aiming his personal

fire hose directly into my eyes. My glasses are so covered with

salt that I could easily season three meals. Ralph is struggling

valiantly to keep our starboard gunwhale above water by constantly

easing the main with each invisible punch. It's my job to do the

same with the jib. The wind has become our adversary and we have

become shadow boxers who counter blindly, unable see the blows

assailing us. The wind is now shrieking through the rigging, the entire

boat shaking in the assault from wind and wave. I wonder when the main

is going to shred itself as there are continuous whip cracking reports

from its violent flogging. It is impossible to tuck in a second

reef as we do not have enough sea room - a large oil tanker lies not

far off our lee.

I cannot say how long

it took us to thrash toward our refuge. It

could have been half an hour, an hour, more than an hour, I do not

know. For me it lasted a lifetime and, in another sense, time

seemed to stop altogether. Everything was happening in the Now

(as, of course, it always does) and, like our fourth day out, we were

again living out the act and scene that our scripts demanded. In

retrospect, I have to say, Ralph offered a splendid performance. In all

his experience, he could not recall a more demanding role.

(Note: We learned the following day that the winds were measured at 40

kts, higher during gusts. For the record, that's the top end

of F8 on the Beaufort Scale.)

Exhausted but not defeated we reach Last Passage, a narrow body of water that separates Great Island from the mainland. You might imagine, as we did, that the wind gods would have taken their bows, departed, and allowed us a much deserved reach to our destination, East Ferry. But our imaginings and wantings deceive us. What should have been an easy reach becomes a beat! And the tide, weak though it is, is foul! We surrender. Bugger Aeolus and praise to Petroleus. The odds of seeing Ralph fire up the outboard are about the same as those of sighting Bigfoot. But fire it up he does. I'm poised with painter in hand and we're within 20 feet of the dock when I hear the engine suddenly go silent. Of course, the foul tide quickly cancels our headway. I'm thinking to myself that the skipper's depth perception needs some adjustment. In an instant, Ralph is straddling the bow, paddle in hand, stroking quickly and powerfully to reach the dock. For whatever reason, the engine has quit on its own. The timing couldn't have been better as a final test of maritime mettle. Ralph passes with the highest of marks for surely, this must have been one of his most demanding days ever. It is the same for me. The hot shower was the

best ever; the Guinness and food never tasted

better; and the live Irish music could not have been sweeter. It

was, indeed, a most cherished evening as the aches and pains of having

engaged so many forces of nature that day began to retreat into the

realm of memory.

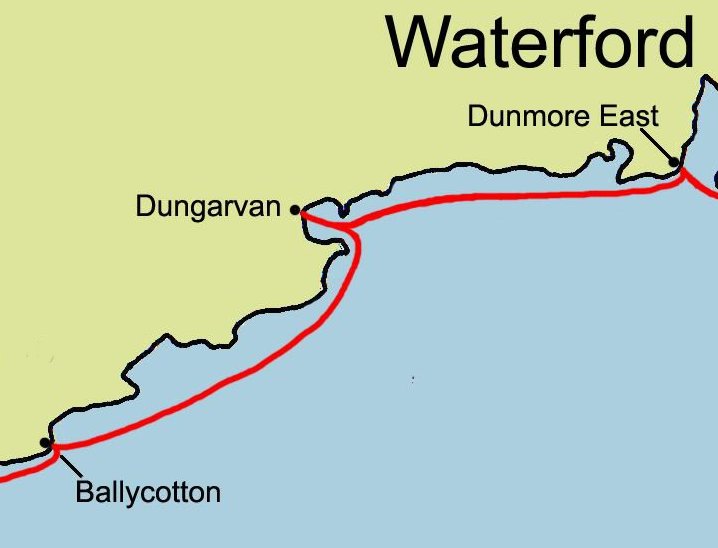

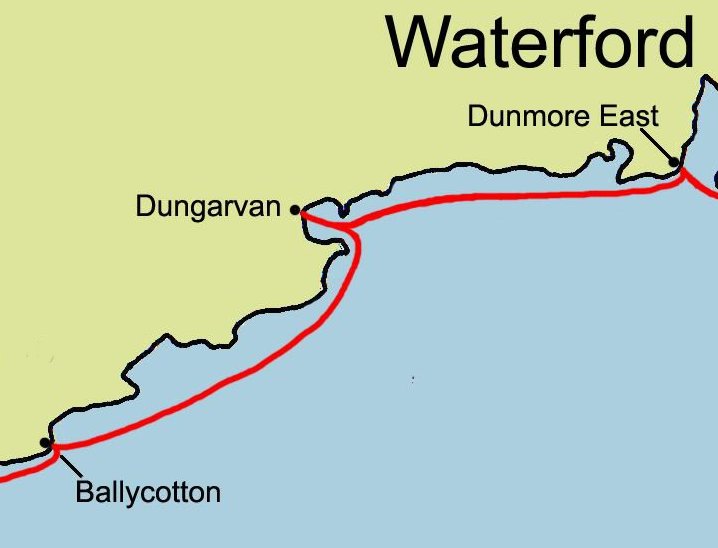

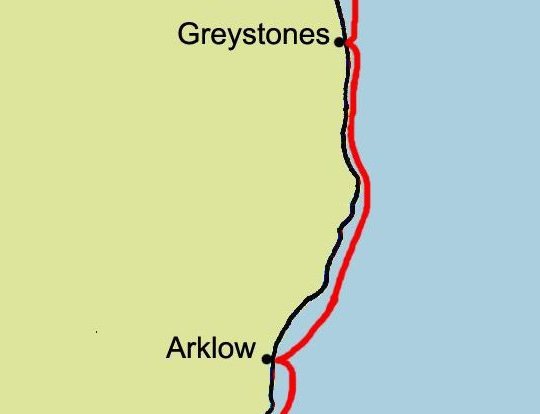

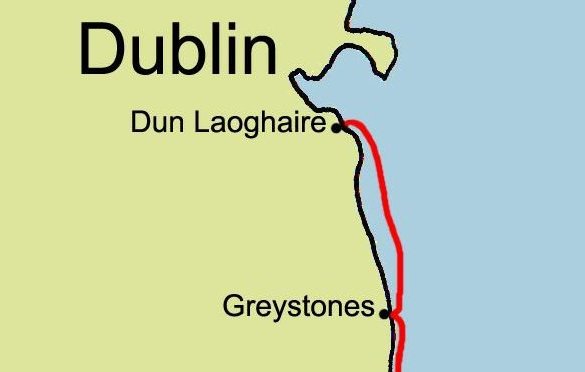

Days 7 - 17: The remaining days of our cruise are more like gentler versions of those before. We call in at another eight ports and one anchorage, each unique and often challenging. There are harbors to enter on falling tides, a beaching to attempt (and abort), channels to "sound" with the centerboard, bridges to "shoot", squalls to soak us to the bone and, of course, delightful Irish pubs in which to salve the days' insults and to share stories with the locals. Ireland is a beautiful, enchanting land, and its people are some of the most gracious, hospitable, and entertaining I have ever encountered. To any of the lovely Irish (and Brits) who might chance to read this modest account, I offer my heartfelt thanks for the privilege of having gotten to meet you. From Baltimore

to Dublin - Part 2

It was a beautiful little vessel, seemingly fragile in its pint-sized proportions. The graceful lines and curves, its traditional draft, were balanced exquisitely between the demands of function and the aesthetics of form. In my brief reverie I sensed the ancient dance between liquid and solid, the Nature-made presence of the one inspiring the man-made invention of the other; how the vessel, in all its iterations, gives reciprocal shape to the yielding fluid; how it liberates bubbles along its sides; and how, in turn, those bubbles form into a miniature boa of foam at the vessel's edge. Yes, before me was, indeed, a beautiful vessel. And to me it was the perfect vessel - a simple pint of Guinness. But this was no ordinary pint. It was a near-sacred libation to celebrate our arrival at East Ferry after surviving a brutal F8 battering when crossing the Bay of Cork in my skipper's Wayfarer.  Upon completing the cruise I often asked myself why two respectfully-past-mature, apparently sensible gentlemen would want to risk such an undertaking. After all, it is a commonplace that the waters off southern Ireland are routinely treacherous and the weather moody. (In 2011 alone there were, on average, 22 rescues per day off Ireland's coastal waters). Even in the most unlikely coastal crannies we often saw large, powerful RNLI lifeboats costing more than a million pounds solemnly poised to intercede on behalf of those who, either because of poor planning, lack of skill, incapacitating injury, or just bad luck, needed assistance to avoid what might certainly become an irreversibly grim fate. The answers to my inner inquiry emerged over time in vague associations of childhood memories. As children we don't intellectualize experiences. We quite naturally lose ourselves in the sights, sounds, and smells of the present moment. Our sense of time disappears. We may not have known the names given to things by adults but that never detracted from our sense of joy and wonder. We didn't need names in order to take delight in the smallest of miracles that, as adults, we come to overlook as ordinary and unremarkable. This, too, was a simpler time before career, family, and mortgage, a time before life becomes complicated. For myself the cruise represented an opportunity to return, if only in an unconscious way, to that naive, childlike state in order to experience everyday things as if for the first time. This was my first dinghy cruise in ocean waters as well as my first experience of Ireland. Nothing was familiar and, therefore, everything was fresh. Our cruise unfolded spontaneously without the trappings of expectations or the inflexibility of plans. For a few weeks we reveled in the rush of the wind, the play of vessel and water, and that childhood feeling of freedom. Each day we sailed into the realm of not-knowing and it was exhilarating. The morning of our departure from East Ferry proved to be as delightful as the day before was dreadful. With very scant room to maneuver and little wind to do so, Ralph, after a few well-executed short tacks, had us nicely moving south through the channel and back toward the Bay of Cork. But today's open sky and moderate breeze proved more than enough antidote to quell my lingering fears of ever crossing this bay again. After reaching the bay proper and changing our course to the west toward Crosshaven, we were overtaken by a RIB skippered by the local sailing maestro, Eddy English. It was he and his crew who took some great pictures of Spree Lady underway. It was also he who confirmed that the previous day's recorded wind speed reached 40 kts, leaving no doubt that we had been dealing with a F8 blow.  The village of Crosshaven is famous for its Royal Cork Yacht Club which was established at the Cove of Cork in 1720 qualifying it as the oldest in the world. The short passage was delightful as a fair breeze encouraged us easily across the bay to our yacht club berth. There were hundreds of visiting boats and crew so it was rather a challenge to locate our assigned berth. After completing the formalities, we were able to watch a race awards ceremony and luxuriate in the sun and clear skies - a complete turnabout from the weather of the previous day. The road along the waterfront was teeming with littoral marine life: street artists, musicians, dancers, singers, all accompanied, of course, by gallons of that most blessed brew - Irish beer. I can still picture the burly fellow in a red satin dress, black lace stockings, and high heels wobbling across the busy street while doing his best to neither spill the beer nor sprain his ankles. We had planned to leave the next day but, once again, the fickle Irish weather was oblivious to our plans. In an act of hope (perhaps it was denial) we went through the drill of making Spree Lady ready for sea but gray skies and persistent rain won out. Before re-converting our craft to sleep mode, we spent an unexpectedly delightful afternoon in a pub engaged in conversation with Pat who, as only an Irishman can, regaled us with captivating sea stories. He was also able to confirm two dismastings during the class race of cruising boats when those furious winds booted us across the bay. And these were fully-crewed boats with keels; not an open dinghy with a crew of two and a centre-plate. The continuous rain of the previous day finally abated and by mid-morning we were able to cast off. The sun reigned supreme and we enjoyed perfect (F4) offshore breezes, broad reaching for hours and planing from time to time. By mid-afternoon we entered the rather minimal harbor of Ballycotton. There were so many permanently moored work boats with lines criss- crossing throughout the harbor that it seemed a perfect confirmation of the latest String Theory. With no apparent mooring buoys available we decided to tie up to a high-walled breakwater using long spring lines which would need intermittent adjustment to accommodate the tides. Aside from being a famous fishing village and seaside resort, the most outstanding manmade feature is the lighthouse located about 2 km from the village. It was constructed in 1851 and its lantern is 196 ft. high. In 1936 a storm produced seas so mountainous that spray was flying over the lantern. After learning this, it became obvious that the height of the seawall we were moored against was, perhaps, not so excessive after all. While Ralph was assessing the options for the morning's departure, he determined that our best one was to simply reverse out of our parking space. There were so many other vessels in close proximity to us and to each other that there was simply not enough room to get underway in the usual manner. He declared that sailing backwards between a selected pair of moored vessels would give us room to fall off on a reach once we had cleared their sterns. And so we did. After all, why disrupt the early morning harbor quiet with two minutes of a buzzing outboard when you can do it all silently and straight-forwardly - or rather, straight-backwardly.  Originally we considered calling at the port of Youghal but since today's winds were as strong and favorable as those of the day before, we pressed on for Dungarvan, another lovely seaside resort town and harbor situated at the mouth of the Collingan River. After a full day of lively reaching along the gradually softening shapes of the Irish south coast, I found myself very tired. Whatever had me coughing for the last eight days and preventing deep sleep definitely had its claws in me now. I knew all was not well the evening of our arrival at East Ferry four days previously when I tried (but could not) offer my thanks to the musicians at the yacht club. Any attempt at speaking was thwarted by some unknown microbial menace. At best, my efforts to communicate mimicked what you hear when your mobile phone is showing half a cell bar. My immune system's defenses had been hacked and, as they say, the disease went viral. As we rounded the point to enter Dungarvan Harbor, Ralph took over the helm. The last hour turned into a nasty beat in F5 winds with a falling tide and our sense of urgency escalated knowing that Dungarvan is a drying harbor. Ralph's technique for navigating up the ever narrowing, poorly marked channel is low-tech but highly effective: he uses his bronze-edged centre plate as a depth sounder. As soon as he feels the center plate hitting the bottom, he calls for a tack. I remember the last 100 meters being the hardest of the entire cruise as we were forced to tack every 15 seconds. Fortunately there is space on the pontoon. We tidy up the main and Ralph heads for the local yacht club for berthing information. I collapse on the dock, completely exhausted, certain that another 50 m would have lead to my burial at sea. When Ralph returns with official berthing permission, we head for the nearest pub and a pint. As good fortune would have it, there is also a B&B with the upper floors designated for guests. A room is available and my credit card materializes instantly. I have no idea how serious my condition is or how long recovery might take. The recent evenings aboard Spree Lady were extremely difficult because, even though the urge to cough was constant, I tried to stifle it for fear of waking Ralph. Not to detract from Spree Lady's accommodations, I have to say that the first evening in the warm, dry, bed with en suite bathroom came as close to experiencing wondrous rapture as I can imagine. I finally felt free to cough without inhibition and, without going into disgusting detail, I will say that the coughing was extremely productive. Images of tiny, periwinkle-sized jellyfish stranded on the shore come to mind. To be honest, there were moments when I felt certain that Ralph would have to enlist alternate crew to finish the cruise; indeed, when my sense of defeat was most intense I almost hoped that he would scuttle the whole thing and call a cab. Nevertheless, a combination of much needed rest, life-affirming Irish breakfasts, and an extended course of antibiotics brought me back from the brink. After five days of my immune system's hard work, we were able to continue our adventure, bound for Dunmore East.  Around mid-morning we cast off the dock lines and eased our way out of the harbor to coincide with the beginning of the flood and the awakening of the day's offshore breeze. We would be retracing our inbound track (which required dozens of tacks) on one, effortless broad reach. Our outbound course would take us toward the lighthouse on the point where we would alter course to the east following the green, rolling shoreline. Today's leg evolved into another glorious day of play on the water. A constant 10-12 kt breeze allowed us to complete the entire leg without once needing to reef - a welcome anomaly for a recovering convalescent. Rounding the point to the Dunmore East harbor entrance looking for a pontoon, we discover there is none. We drop the main and under reefed Genoa we head directly for shore - as in directly toward the big rocks on the shore. Straddling the bow I fend off with my feet hoping to prevent Spree Lady from taking it on the chin. Expert approach by the helm, inertia absorbed, and with painter in hand, my task is to fend Spree Lady off the rocks while Ralph scouts out overnight berthing options. There are few. We are directed to the inner working harbor clogged with numerous closely spaced fishing boats and literally no room to maneuver under sail. This is clearly one of those occasions when the skipper has to change hats from purist to pragmatist. So Ralph fires up his largely ornamental outboard and we thread our way into an already densely populated crowd of working vessels. Even though there's no apparent "room at the inn" we're able to take advantage of our diminutive size and go where no dinghy has gone before. We secure Spree Lady in her new niche and set out to enjoy a walking tour of the town taking in its spacious parks, calm-inducing overlooks, the Grand Haven Hotel, and dinner at the Spinnaker Restaurant. After a peaceful night's sleep we are awakened to the sound of hundreds of screeching seagulls and marine diesels belching to life as the local fishermen expertly maneuver their vessels out of the crowd toward the sea. We soon follow after our usual breakfast of muesli, bananas, and a hot cuppa tea. Our course will be directed east toward Kilmore (below) , a small village in south County Wexford.   Like every other on our cruise, this day begins with a minor sense of adventure, of wondering what it will bring - so very unlike the experience of commuting daily on the M1 to one's workplace. And today we are not disappointed. About an hour into the sail, Ralph puts up the spinnaker which is a first for me on a dinghy. It becomes one of the most exhilarating moments of the entire cruise - and one of the most exhausting. Ralph lets me helm for about 2 hours. We are pursued by legions of white horses driven by the persistent F4 winds. We easily surge down the faces of the small 3 - 4 foot seas often surfing at 9.5 kts, occasionally faster, as our bow comes unnervingly close to impaling the backs of the waves before us. Perhaps it was more than "Six Degrees of Separation" but never before has so much concentration been required to avoid either jibing or broaching. By the time Ralph douses the spinny, the wind was up to F5 and I am a wreck. The entrance to the harbor was narrow enough, guarded as it was by a high breakwater, but made even more challenging by the large fishing vessels that towered above us, effectively blocking our wind. Getting through became another unexpected test of seamanship. Simply running the gauntlet is one thing; tacking through it with barely enough room to maneuver is quite another. After near interminable tacks in the variable, shifting, airs and negligible progress we finally emerged from the fishing vessels' wind shadow and now had more than enough wind to lay a short course toward a pontoon and possible berth. With as much wind as there was, many Irish heads turned our way to watch what in Kilmore is apparently a very rare occurrence - berthing under sail. We treated ourselves to hot showers and a well-deserved, deliciously decadent dinner at the Silver Fox: baked salmon, braised vegetables, and cheese cake with ice cream and coffee for dessert. A brief walk around this super tidy village included a good scare by a local dog that revels in scaring hapless tourists. His unexpected presence and loud, startling bark instantly accelerated my digestive process (though not to the point of embarrassment) but his wagging tail eventually gave him away. June 29th: Our morning departure required just as deft a hand at the helm as our arrival since the airs were very light. While the voices in my head were silently screaming "just start the outboard", Ralph was effortlessly merging into the day's adventure with lots of tacks, occasional paddle strokes, and Viking-like determination. We did, at last, clear the breakwater and set course for Wexford, a city with a fascinating history dating back to about 800 AD. Once out of Kilmore Harbor we had a delightful passage east.  We surfed for hours under full main and partial to full Genoa finally rounding Carsore Point thereby simultaneously leaving the Celtic Sea astern and entering into the St. Georges Channel of the Irish Sea. We sailed very close to shore in order to take advantage of smooth water and to minimize the effect of the increasingly stronger counter current. It seemed at times that we were no more than 10 - 15 meters from shore and no more than 1 meter above the large boulders on the bottom that were clearly visible to us as we skimmed by. This long stretch of shore-hugging finally brought us to the outer limits of Wexfod Harbor. At this point we had to surrender our beam reach for a very wet (wind now against tide) beat requiring a single reefed main and reefed Genoa. The harbor is natural and lies at the mouth of the River Slaney. In earlier times it was considerably larger than today, up to 10 miles wide with mud flats on both sides known as the North and South Slobs from the Irish word slab meaning mud. Further into the harbor we became intimately familiar with the Slobs as our progress was continually punctuated by warnings from the depth sounder - aka Spree Lady's centre plate. By this time a squall was approaching, the rain lashing us in sheets. We eventually discovered that the starboard self-bailer was no longer functioning and a fair amount of water began to collect in the leeward bilge. As they say, showers pass, and this one was no exception. While there was some relief to be found in the cessation of the rain, there appeared to be no berthing facilities available for small craft except west of Wexford Bridge - a bridge too low to transit without lowering the mast. To accomplish that, Ralph approached an unused mooring buoy which we clung to as he proceeded to lower away. With mast secured we motored under the bridge upriver to the local sailing club. Over a much-yearned-for Guinness, we discuss the berthing options with club members and are graciously granted permission to tie up to the pontoon for the evening. Before enjoying a hot, delicious, skipper-prepared dinner of pasta and chili con carne, we are treated to a flurry of sailing club activities involving a small fleet of the youngest skippers I have ever seen sailing little prams, all of which have safety lines tethering them to shore. Both Ralph and I are amazed at how accomplished these tykes are at handling their craft and suspect that they'll be collecting racing trophies soon enough. June 30th: The departure from Wexford is to become a living example of what I'd only read about in the lore of dinghy sailing. Our course offered a fair wind and fair tide. Ralph decides that we may as well save all of three teaspoons of fuel and just "shoot the bridge". That is to say, lowering the mast under sail in order to transit the bridge and then raising the mast after clearing it. If not done properly, things can go terribly wrong in a hurry. We get underway with Genoa only, boom deliberately unshipped and stowed. Once clear of the bridge we raise the mast, ship the boom and raise the main. All goes smoothly and there's a decent sense of satisfaction in having performed one of those rare maneuvers that give depth to one's seamanship. Often when dinghy sailing, the skipper can cut corners - literally - when following channel markers. Not so today. With a falling tide, we run out of water numerous times on those ancient, notorious Slobs. We are actually forced to seek out the navigable channel just like common sailors. It's almost humiliating. If we could have displayed our track on a GPS, I suspect it would have looked much like a 3-year old's Etch-a-Sketch. It was definitely longer but way more scenic and we saw hundreds of seals and shore birds atop the sandbars we were trying so hard to avoid.  Finally clear of the shifting, wet sands we turned north on an easy F 2-3 reach. This was the first stretch of coastline that did not afford us a predictable harbor or natural refuge within our sailing range. The next available was Arklow, but that, even with a fair current, was quite beyond our reach. We would be improvising today. After several hours, the wind picked up to about F4 and the air turned quite cold. Our attention becomes fixed on finding a suitable place to beach just as was done in scenes from Saving Private Ryan, a film shot (I'm told) very close to our present location which is near the town of Polduff. The shore is mostly comprised of rough shingle and rises rather steeply. Ralph selects what appears to the best of far-less-than-ideal options and we make ready for the landing with rollers, lines and other appropriate tackle. As we both struggle to align Spree Lady with the rollers, it soon becomes obvious that, because of the unruly surge and significant north-going current, I will not be able to keep the boat perpendicular to the shore long enough for Ralph to properly position the rollers under the hull. Repeated attempts confirm this. It's one thing to beach a 500 lb. vessel on a gradually sloping, sandy shore; it is quite another to do so in surging water against a steep, shingled shore. Wet and cold, we abandon Plan A and opt for Plan B. We don't actually have one yet but hope there might be something around the next corner a few hundred yards north. There is a small, private slipway but nothing offering any protection when tied up. On to Plan C which is to keep going a bit further. Nothing obvious appears and Plan C evolves into Plan D - anchoring. But before committing to that, Ralph once again carefully scans the shore mentally exhausting the odds and probabilities for another go at Plan A. Nothing seems worth the effort or risk. Plan D it is. This will be our first unprotected anchorage and it becomes noticeably more challenging to transition from cruise mode to sleep mode in the absence of a pontoon on which we can temporarily stow gear while re-arranging things. Coupled with the lively rolling and pitching of the boat, I was retrospectively grateful for all of our previously protected berths. Even so, nothing was lost overboard and Ralph served up a much appreciated meal of chicken stew con pasta, Tuborg beer and homemade bread. As the wind subsided and the rolling diminished, sleep came quickly and soundly.   July 1st: Before weighing anchor for Arklow, Ralph wanted to get a few shore-based pictures of Spree Lady at anchor off the east Irish coast. Since the anchor line is handily stowed on a rotating drum under the foredeck it was easy to veer the line to its limit which, as coincidence would have it, allowed Spree Lady to come within several feet of shore. Perfect! Ralph took a stern line ashore in case the current or wind shifted. I hauled in on the anchor line to keep us safely offshore and he secured the stern line. Ralph scouted the terrain and shot some great photos (above) from the small bluffs overlooking the shore. Before getting underway we, of course, had to reverse all of the foregoing from hauling in the stern line, paying out the anchor line, heaving it back in to gain a little sea room, changing from sleep mode to cruise mode, weighing anchor, and finally, making sail. Uncharacteristically, we encountered very light airs and spent nearly five hours covering only thirteen miles. The wind actually died just as we reached the harbor entrance at Arklow and there was little reluctance to press the outboard into service. As we proceeded up the River Avoca, it was obvious that Arklow had once been a large and thriving commercial port. There are huge concrete quays lining the channel and, with a bit of research, I discover that the sail training vessel, Asgard II, was built here as well as Sir Francis Chichester's Gypsy Moth III. We eventually find a pontoon not far from a local marina and yacht club and well past the uninviting commercial docks. A Danish lady on a large sailing yacht berthed ahead of us kindly shares the code to the restrooms and showers. I remain in her debt forever as I have not been ashore for two days - to answer a call of any kind. We share a lovely pub dinner with her and her Norwegian husband both of whom will soon be venturing into the realm of world cruising.  July 2nd: Well rested and well nourished we execute a leisurely departure around 11:00. There's a useful southeast F3 wind and a strong favorable current. It's actually sunny and we make good speed until the tide turns and we begin to slow appreciably. Ralph puts up the spinny to compensate. The tide is definitely foul by Wicklow Head and there are visible rips rounding the point. Once rounded, Ralph calls for a jibe. I bungle it when handing off the helm and we accidentally jibe all standing - or in my case, falling, over to end up on the lee side of the boat. I am sorry, embarrassed, and lucky that nothing fouls, breaks or results in a capsize. Ralph sorts out the mess, and retrieves the spinny. We have an agonizingly slow run toward the shore of Wicklow. Our speed has dropped from 6.5 kts to a mere 2.5.  Finally, at 10 meters off the beach (give or take a few - we're damned close!) our speed increases and Ralph again calls for the spinny. No doubt the current at last reaches slack and we enjoy a fine 2-hour run to Greystones Harbor, our penultimate destination. Within the towering concrete walls forming the breakwater we see a slipway and a single yacht, side-tied to one of the inner walls. There are no pontoons nor marina as such. Another moment of serendipity. It turns out that Monica Schaefer has spotted our arrival from the vantage of her lovely, hillside home and, not only does she greet us with two bottles of beer, she also manages to arrange for our rafting up to the beautiful yacht for our last evening before heading the next morning to our ultimate destination, Dublin/Dun Laoghaire. We share one of the best cups of tea ever with Percy and Aine, owners of the yacht and leave Spree Lady safely nestled against it. A run of twenty-five miles without reefing or major catastrophe of any kind. It was good day to be sure and made even better with a fantastic barbecued dinner at Monica's and the camaraderie of fellow sailors. It was a shock and luxury to reflexively stretch while sleeping and discover that I can actually do so. Three weeks of wriggling into a mummy bag has a defining influence on one's sleeping habits.  Our last day's official sail would take us from Greystones to Dun Laoghaire, a suburb harbor just a few miles south of the greater Dublin Harbor which serves thousands of large commercial vessels and pleasure craft. Dun Laoghaire is also the staging area for this year's Regatta which attracts sailors from all of the UK and Europe to compete in the various class races held during race week. Before casting off, we once again were treated to the cordiality and hospitality of Percy and Aine in their cockpit, a space capacious enough to accommodate most of Spree Lady. We said our farewells and fair winds and were able to catch the light, early morning breeze after only three minutes of motoring. It was a gradual, gentle morning on the water beginning with a slow broad reach/run north. As the wind picked up, Ralph hoisted the spinny giving us all of 2.5 kts. The wind then dropped followed by the spinny. However, within the hour the wind picked up again and were were skipping along at 3 - 4 kts under main and spinny. A continual run brought us into a kaleidoscope of hundreds of boats on courses like intermingled round-a-bouts at rush hour. They are on every possible point of sail and I am extremely nervous about being among so many boats so close to us. We realize soon enough that to avoid an outcropping of rocks, we need to jibe the spinnaker which I was also trying to avoid. The need to avoid the rocks is more compelling than avoiding an accidental jibe. Better a tangle of sheets and guys and Dacron than explaining damage claims to Ralph's insurance company. Ralph once again sorts things out and then takes over the helm to thread us through the moving maze of masts. The skipper brings Spree Lady in for another, ho-hum perfect landing which turns out to be about 50 m from our assigned berth. Ralph, in predictable consistency, foregoes firing up the outboard and paddles to the new slip. I would bet anybody in the harbor a couple of pints that he is completely devoid of stockholdings in BP. Endings are always difficult for me inasmuch as they embody a medley of mixed emotions. There is the sense of great satisfaction and accomplishment as well as the slight sense of loss and having to let go. A goal at last achieved and by being achieved, necessarily abandoned. To be replaced by another …. perhaps. But the next can never be the same and I wouldn't want it any other way because out of that uniqueness arises life in this here and this now. That's the joy I carried away and can re-live, if only in memory, at any time. Would I do it again? Perhaps. My learning curve was as steep as the market crash of '08 and I now know I was way too inexperienced to be considered competent crew for such an undertaking. In a less critical light, I was initiated into this rather elite class of sailors by a fine teacher and learned an enormous amount about open ocean dinghy cruising uncovering some weaknesses and strengths in the process. And as meaningful as the sailing experiences were, I cannot help but recall the underlying sense of kinship and kindness that touched us each day in the harbors, pubs, markets, and government offices. In Ireland, courtesy seems natural. Cut off from newspapers and TV as I was, perhaps my social sensibilities were sharpened a bit by the creative, resilient, real-world people of Ireland rather than the virtual-world people of the media. This I know for certain: I long to visit Ireland at least once more this lifetime, either by land or by sea. And my first quest upon arriving will be to find an old pub overlooking the sea where I can re-experience my love affair with that beautiful, frail little vessel and its contents - a simple pint of Guinness. Brandon McClintock

W3576

Footnote from Ralph Roberts. Brandon is perfectly correct to deduce that I have absolutely no shares in BP, but the real reason I prefer to maneuver under sail is that I feel in more control of the boat than using the power of the outboard. It is only too easy to turn the twist grip throttle control the wrong way and spurt forward with disastrous consequences. Far safer to completely furl the genoa to take it out of the sail equation and then feather the mainsail to reduce speed as much as is needed before finally turning into the wind at a snails pace, to stop precisely by the side of your chosen landing spot on the jetty - negating even the need for a fender to be put over the side beforehand. If the approach has to be downwind then the main can be lowered first to approach on genoa only, furling in the genoa as required to slow down to a speed where the boat can be brought to a stop simply by rounding up into wind. It would however have been more seamanlike to have sailed out of Kilmore harbor with the outboard idling in neutral, so that I could have easily engaged the forward gear when I had insufficient wind to complete a tack and needed some additional forward momentum.  Brandon |