| Subject: Uncle Al tries to explain

upwind angles to Andrew Haill -----

Original Message -----

From:

Andrew Haill (W9657)

To: Al Schonborn

Sent: Tuesday, November 27, 2007 11:52 PM

Subject: a

question of angles

Hi Al

cheers,

Andrew

-----

Original Message -----

From:

Andrew Haill (W9657)

To: Al Schonborn

Sent: Friday, November 30, 2007 6:53 PM

Wow ... that's great, Al ...

thanks. Adding that to the Tactical considerations section

of the WIT would be good. Actually the WIT is another hot button

to consider.

I'll have to give this some serious digestion... but I see if the wind headed both boats, the leeward one is now ahead ... Theoretically both boats will tack on the header; is there effectively any gain towards the mark? do you keep some? ... if for no other reason, I suppose the front boat needs to tack to consolidate this gain? Which brings up "cross em while you can". Glad you like the knot thing... I stole that off the Thunder Bay YC site myself. cheers,

Andrew

-----

Original Message -----

From:

Al Schonborn

To: Andrew Haill (W9657)

Sent: Monday, December 03, 2007 12:14 AM

Hi, Andrew:

Good thinking about the

WIT button - done!

Thanks.

Regarding the shifts:

Over 90% of shifts are oscillating shifts, i.e. shifts that swing

back and forth. So, as you say - all else being equal - both

leeward/ahead and windward/astern want to tack if they are knocked. If

the shifts are indeed swinging back and forth, windward/astern has only

to wait for the return oscillation, and when both tack back to

starboard, the boats are even again. In other words, as long as

both boats stay on the favoured tack, and windward/astern doesn't let

leeward/ahead cross him, he's OK.

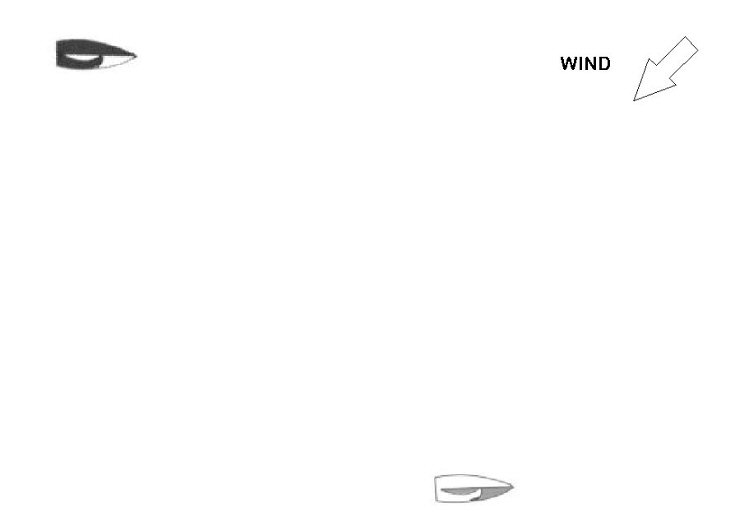

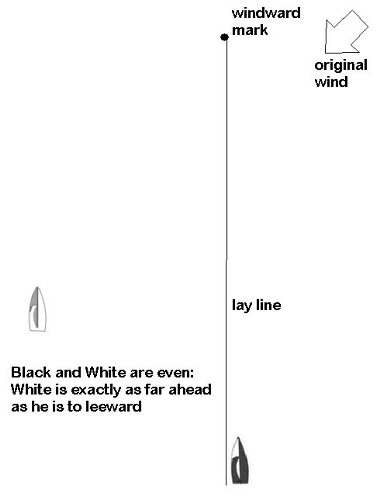

But if w/a (Black

above) holds the knocked tack, then Black is confirming l/a's (White above) gain ...

... by letting White

cross, and if White likes, he can ...

... tack to windward

and ahead of Black who was formerly windward/astern. Once you put a guy

to leeward and astern of you, no shift can let him pass you any more.

He can pass you if you hit a big dead spot or he gets a different wind,

but those things are rare, and even then, can usually be managed

without losing the boat astern and to leeward, if the boat ahead keeps his eyes open.

This of course,

simplifies the situation to an America's Cup format, whereas fleet

racing is far more complex. In the image above, for instance, White

would be unwise to tack back onto the knocked tack unless he

specifically needs to make sure he beats Black, and losing

distance to other boats who play the shifts more correctly is

immaterial. In any case, no one ever gets everything just right. Which

is what makes racing a bit of an art form and keeps it interesting, but

the underlying angles principles need to be the foundation on which one

builds - a bit like learning to skate before one adds the dekes and

other nifty moves in hockey.

About the mark: You want to think

more in terms of shortening the distance you need to sail to reach the

windward mark, rather than where the mark is. Marc and I tend to

think of the mark only insofar as it creates lay lines, port and

starboard, which - under

normal circumstances - we

want to avoid as long as possible. I have tried to explain the reasons

for this overriding paranoia about lay lines below:

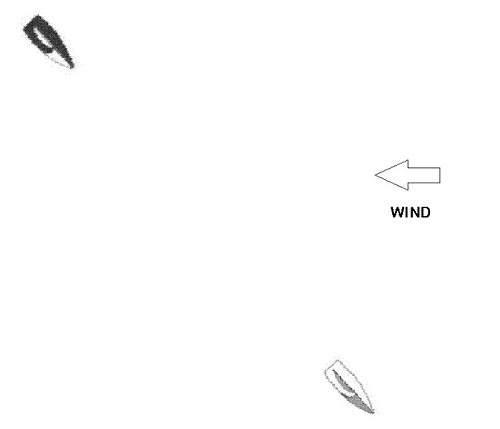

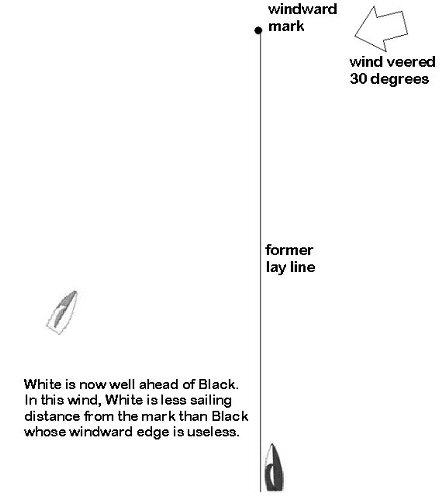

Once you hit the lay

line (Black in image above) you are out of useful

options if any further shifts occur. Look at the two main

possibilities:

If there is a lift for

your tack and you are already on the lay line (Black above),

you will merely be overlaying the mark while a guy that was even with

you but to leeward and ahead, i.e. short of the lay line, can - unlike

the guy on the lay line - cut some distance sailed by pointing closer

to the mark. Black can foot off and go a bit faster on his reach than

White, but that will not make up for the extra distance Black is having

to sail. Pointing up would be even worse for Black who would then not

only have to sail even more extra distance but would also give up what

little extra speed he might get from reaching as opposed to sailing

close-hauled.

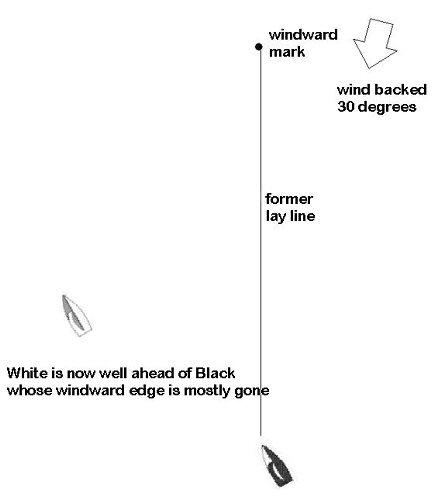

If both Black on the

lay line and White to leeward and ahead get knocked (above),

they can both tack. Then, under normal circumstances, a return shift

brings the two boats back to even. But not if Black started on the lay

line, and White was leeward and ahead below the lay line. In that case,

the return shift only lets Black overlay the mark when he tacks back,

and Black has wasted much of the distance that he put in after tacking

on the knock. All the windward edge Black had, the edge that was

keeping him even with White (leeward/ahead) is now useless, because

White, after tacking back

on the return shift, is

now probably laying the mark and doesn't need any more windward

distance. If Black chooses not to tack, he is letting White cross

him and confirm his gain. A no-win situation for Black, and most time,

the best that Black, the early arrival to the lay line, can pray for is

no shifts, which is the only way he won't lose. And barring pure bull

shit luck, there is no way that Black will gain by having hit the lay

line too soon.

30° shifts are

rare, to be sure, but we got those at this year's Ontarios in Ottawa,

as you may recall. And of

course there are exceptions to the dictum: Avoid the lay line as

long as possible. I just finished writing about one that applied

in Saturday's racing at the 2007 NA's at TSCC. These exceptions are

usually geographic factors that cause permanent wind bends or better

wind out near one lay line or the other. But those cases are rare, and

can be learned fairly easily, especially by those who keep race diaries

(as I used to - now I'm just too lazy - and/or busy with camera and web

work). On other days, guys will hit a lay line early and make out like

bandits, having gotten a different, better wind. But relying on this is

like relying on the lottery. Neither pays off nearly often enough.

An interesting mixture

of Sail the lifted tack and Avoid the lay lines can

occur on a course where the windward mark is significantly skewed

from being dead upwind. One such instance used to be our National

Cruise Race when it was held each year (1961-1988) on Trout Lake. We

would start across the lake from the McNutts' and sail our first leg of

perhaps 5 miles to the very west end of the lake to a mark in Delaney

Bay near where we now launch for the Poker Race. More often than not we

would get a nice hiking breeze from the WSW that was spiced with the

odd short stretch of a veered, more westerly wind. This long, long beat

taught Julia and me a very valuable shifts and lay lines lesson which I

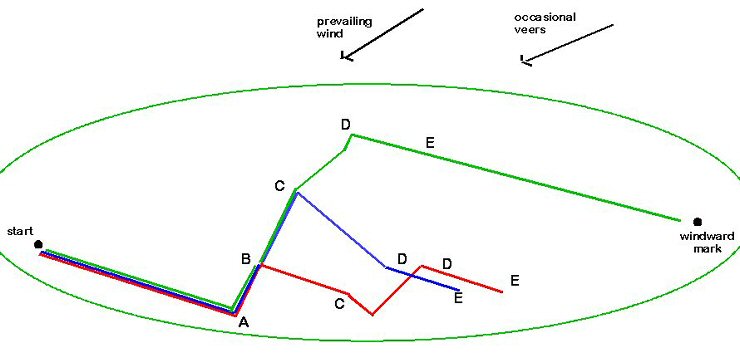

have tried to diagram below:

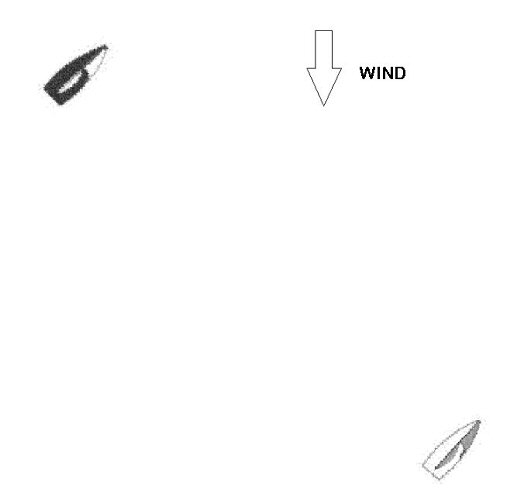

Given the fact that the

wind is blowing at a significant angle to the rhumb line (straight line

from mark to mark), it is a given that we will spend far more time on

one tack (port, in this case) than on the other. It soon became clear

to Julia and me that we needed to hoard our starboard tack time if we

didn't want to end up on the port lay line way too early. Most of our

fellow sailors never did develop an appreciation of this

crucial reality. The average guy did what Green does in the diagram

above: Sail port until you're forced to tack by the shore. Since there

were few shifts, starboard did not feel terribly unfavoured, and it was

easy for Green to proceed past point B and on to C. Red, meanwhile,

sails to hoard his starboard tack time and not spend it unless

absolutely necessary. Therefore, he tacks back to port at point B, as

soon as he has enough "sea" room to stay on port for another little

while (how soon Red tacks back to port will depend on how much he

thinks he's losing each time he tacks). By the same token, if Red

meets a starboard boat, it pays for him, in such a situation, to

bear away rather than to tack and pin himself in a position where he

wastes minute after minute of precious starboard tack time. All this is

pretty simple, if you sail with the constant mantra: Avoid starboard

tack until the starboard lift comes along.

In the diagram, I

have made the - short-lived as it always was!! - westerly shift

kick in when all three boats reach point C. Until that point, Blue and

Green have sailed the identical course. But here, I have made poor Blue

tack just as he was about to get the starboard lift - something we've

all done, and Blue should, of course, immediately tack back under

normal circumstances. But I then forced Blue to stick to the knocked

port tack (the Shit! We've tacked now, so that's that syndrome). Green gets his

lift at point C and is naturally happy about this and continues on

starboard. Just to show Red is not flawless, I have had him sail into

the knock before tacking. Not too long afterwards, the westerly slant

passes on through and the wind returns to its prevailing direction as

the boats reach point D. Green and Red tack in textbook fashion, and

remain dead even - Green being exactly as far astern of Red as he is to

windward of him. But you can see that Blue is already behind Red, and

therefore behind Green as well - all because he sailed on port when

starboard was lifted. Red is smiling from ear to ear however - a

nervous smile perhaps, because from time to time Green seems to be

getting more wind and/or a major port tack lift way over there on the

other side of the lake, but that was good for building our mental

toughness - and it became easier as year after year, none of these

boats ever did pass us as we short-tacked along the north shore.

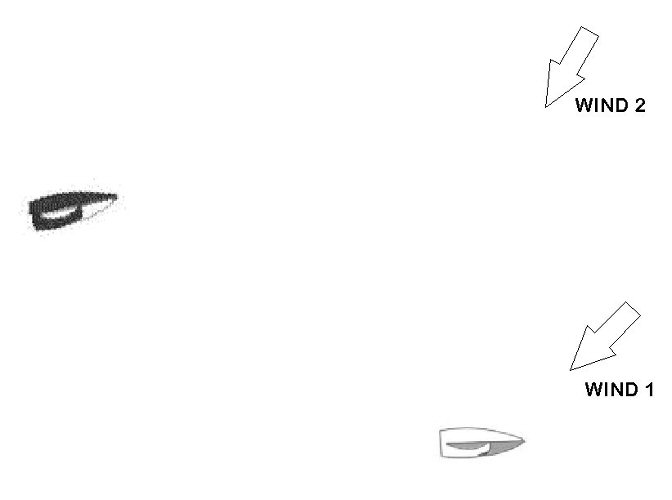

In the only marginally

simplified diagram above, the reason for Red's smile is that Green has

now reached the port lay line and can no longer benefit from the

perhaps half dozen minute-long starboard lifts that are guaranteed to

come along between here and the windward mark. And each time one of

those eagerly awaited shifts hits - no

need to even tell Julia we're tacking, she's been waiting for the port

knock as eagerly as I, Red will tack and add to our lead over Green who

no longer has anything useful he can do with those starboard lifts,

being on the port lay line as he is!! Of course, once Red gets

closer to the mark and reaches a point where the mark is directly

upwind, he no longer has to be leery of spending his starboard

tack time.

Actually, I have just had a revelation:

Every race we sail in, has this same element that needs to be managed.

The more we get out to one side or the other of a beat, i.e. the closer

we get to a layline, the more our race has become what I just described

above: our time remaining that we can usefully spend on one tack

or the other becomes shorter and shorter as we get ever nearer

to a lay line. And as that happens, we need to be more and more

leery about wasting that little bit of remaining time on tack X for no

good reason. The though process should go something like this: If we

are not on the tack towards the lay line, good! And we won't want to be

on that tack unless there is an overpowering reason to squander what

little time we have left for that tack. If, God forbid, we are actually

sailing towards the lay line and getting close to reaching it with

significant amounts of sailing still to be done before we reach the

windward mark, then we should tack right now, unless there is an

overwhelming reason why we just cannot afford to!!

Getting close to the lay line at some distance from the mark should make all of us actively uncomfortable! Doing so for no justifiable reason, makes it look like one does not really know what one is doing. After a race in which I have let myself get to the layline too early, I still come in embarrassed, regardless of whether we won or lost. Even at the NA's this year, I was sure to explain that we had a good reason/excuse for banging the left corner on the Saturday. Hope this helps,

Andrew! I had fun creating it but it has used up all the time I was

intending to put in on the Weekly Whiffle. So I think I'll

throw this material in there tomorrow morning still, in

preparation for its going into the WIT.

Take care,

Uncle Al (W3854)

|