| A

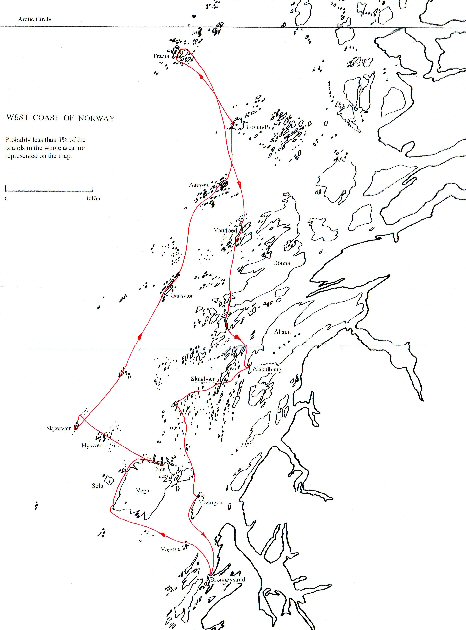

Norwegian Cruising Experience Ralph Roberts, Wilhelm Munthe-Kaas and Blunderbus (W1309) explore some islands off the coast of Norway just south of the Arctic Circle in mid-July 2002 Part 1 of a log by Ralph Roberts .. |

Casually

looking up from the airport coach as it stopped to let off some

passengers on

the outskirts of  I had met

Wilhelm the previous summer at his holiday ‘hytte’ (cabin) on the

shoreline of

one of the many islands near Kragerø. He had mentioned that it

was his ambition

to cruise ‘Blunderbus’ – the Wayfarer he had bought from the renowned

UK

cruisers, Roger and Diane Aps – along the west coast of Norway, just

below the

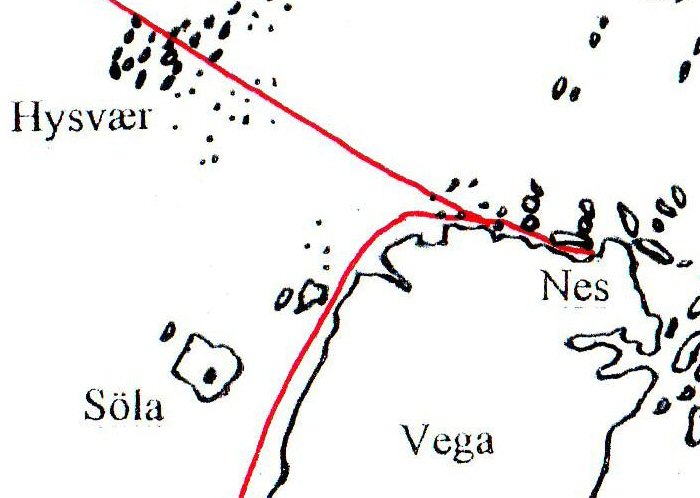

Arctic Circle (see cruise overview above,

or click here for the

full-size version). It was an area he had briefly

visited on a cruise to

Wilhelm

had been impressed with the Harken jib furling system I had on my boat

when he

had visited me in the Spring, and I had brought along the same system

for Blunderbus. As it was a

very long drive to our destination, however, Wilhelm

had decided not to spend time fitting this on the boat before our

departure,

and we headed straight off to Brønnøysund from the coach

terminus. Wilhelm was

determined not to waste any time in getting our

Norwegian cruise started.

On the road beyond

Trondheim around 30 minutes past midnight, with the sun

about to dip below horizon

...and the mist from the valley we are about to descend into, just showing above the tree line. |

|

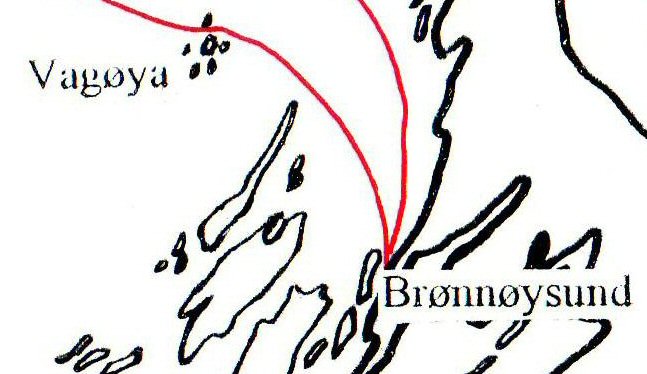

Day 1:

Brønnøysund to Vagøya

We

didn’t reach Brønnøysund until late in the afternoon,

where we first stocked up

with food from the local supermarket before finding the marina to

launch the

boat.

Wilhelm (red

jacket) prepares to load all

the

gear for our two-week trip after

launching Blunderbus at the

The view is looking north into the direction we are about to sail.  Wilhelm holding the

outboard - all other

items of gear used on the trip are laid out on the pontoon.

(Picture taken after our return).  All our gear stowed

immediately prior to

our departure. The red and black crash hat was in fact

worn only once during the trip - on our only day’s sailing into a strong headwind.  It was gone 1830 by the

time we had packed the

boat for our two-week cruise, which would have been far too late to set

off on

any trip in the UK. But with nearly 24 hours of daylight this near the

Arctic

Circle, we were able to set sail to the Vagøya group of islands,

where we were planning to camp for the night. There

was a good breeze and bright sunshine, so we enjoyed a pleasant

five-mile

beat to a

suitably sheltered bay on the second of the islands we approached.

Landing at

nearly 2000, close to low water, we anchored the boat bow and aft.

Extra care being

taken at this stage not to make the first mark on the perfect finish of

the

boat, either inside and out.

Wilhelm considers

whether his newly

painted and varnished boat will be secure. It is near to low tide,

and he is concerned that the sharp stones and shells up to the high water mark could puncture the inflatable rollers. A

grassy area slightly sheltered by a bank and well above the high water

mark

made a good place to pitch our tents. Normally it doesn’t take long for

the

local mosquito population to hunt down any juicy, fair-skinned English

quarry.

However, I had not forgotten the nuisance they had been in

Wilhelm’s tent on a

grassy area kept well

shorn by wild sheep. The position was sheltered by a bank, from which

the photo

was taken. In the background is the mountain range on the mainland,

with many

peaks above the cloud line.

|

|

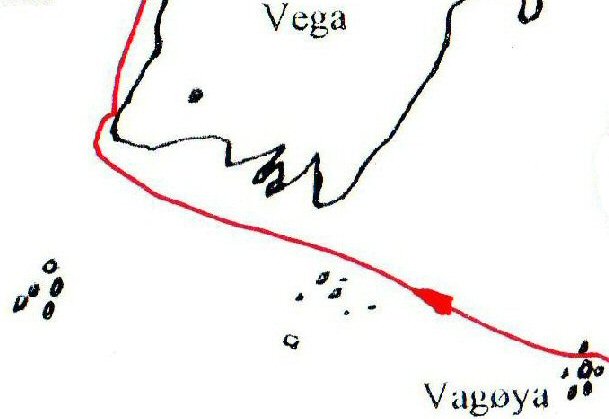

Day 2: Vagøya

to Vega

The next morning was

fine and warm, though a little

cloudy. We packed the boat rather

more efficiently than we had the

previous evening when setting off had been more important than worrying

too

much about stowage. We were away by 1130, hardly an early start

by normal

cruising standards, but we were sailing with the inclination to gain

the most

pleasure and enjoyment from the trip, rather than to try to sail as

many miles

as possible. We also had the advantage of having no particular time by

which we

had to arrive at our destination before darkness.

Winds

were generally light and

variable for another five-mile sail - this one to Vega. We started and

finished by motor

sailing,

whilst enjoying a pleasant following breeze during the mid-part of the

day’s

cruise. Rounding the southwest tip of the island, we investigated the

first

cove, only for Wilhelm to decide that it would be too rocky at low

tide.

Vega landfall:

Wilhelm has dropped a

stern anchor and secured the bow to a

rock ashore.

Though the strength of the tide wasn’t as great as that around the  With very little

breeze in the lee of the

mountains, we motored round the next headland to find what appeared to

be a

sandy beach with a grassy area beyond, that looked ideal for camping

(to the

right of the

centre of the picture).

A

little further along the rocky shoreline at the next inlet, a welcoming

sandy

beach appeared, and we made our way into a much more suitable landing

place. We

rolled Blunderbus up to the high

water mark. Wilhelm had seen this done for the first time at the UK

Cruising

Conference the previous Spring, and had bought some inflatable rollers

especially for this trip. He was still a little surprised at how easily

only two people could perform the task. The shallow gradient made this

possible

without the need for any winch system. Rolling the boat beyond the

tide-line

removed any concerns about anchors holding, the wind

changing

direction, or the boat grounding at low tide.

... |

|

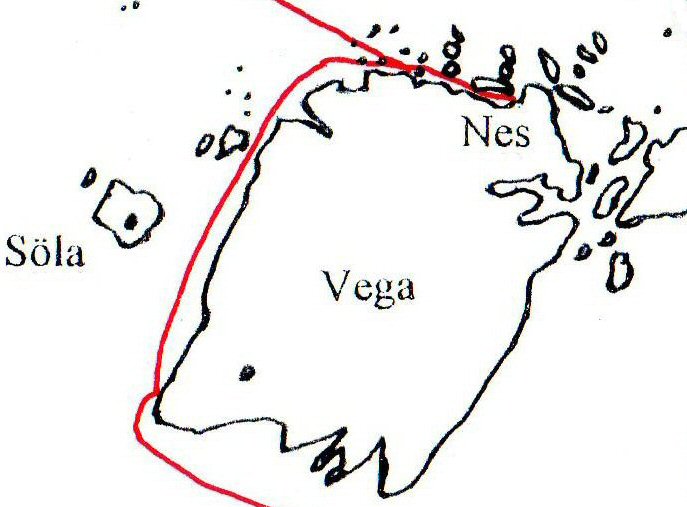

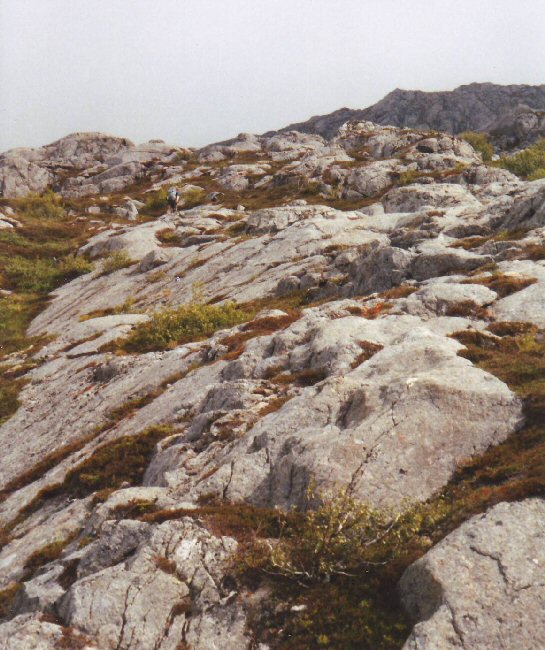

Day 3: Vega

Wilhelm’s

ambition for the trip was to climb as many mountains of his very

beautiful and

wonderfully rugged country as was possible during the trip. Next

morning

therefore, we hiked off on an intermittently marked track which Wilhelm

expected to lead us to the high ridge of the mountain on the

south shore

of the island.

Blunderbus rolled

up to the high water

mark, with our tents pitched immediately behind.

Low cloud is obscuring the mountain Wilhelm aimed to climb.  Wilhelm is barely visible, adjacent to the top of a grassy patch on the far left. The mountain peak is in the distance on the right. After a

1½ hour walk, during which we had ascended to the lower

foothills, the

track appeared

to drop back down toward the coast – a route that quite appealed to me

as I

remember, since my legs were beginning to tire from the constant

climbing.

Wilhelm

decided at this point, that it would be better to continue upwards, and

join the trail at a higher point. Feeling that I would hold Wilhelm

back if I

ventured further, I suggested he continue alone, and watched him

disappear

into the distance, like a mountain gazelle released from a cage.

I

was happy to sit and relax for a

while. Although the sky was somewhat grey and overcast, the views over

the sea

were still spectacular, with a cluster of small islands immediately

offshore,

most only a meter or two above the sea until they finally disappeared

from

view, and there was nothing but the vastness of the North Sea beyond.

Looking out to the

The photo makes the day seem more overcast than it actually was. The group of the small islands in the far distance could easily have been mistaken for a school of whales. Having

taken my fill of the beauty and peacefulness before me, I wandered back

to our camp at a leisurely pace, stopping quite frequently to take in

the views at

the top of any vantage point, and to pick wild blueberries and the

local moltebær. These are considered

to be quite a delicacy in

Wilhelm

returned a little after 1700, just as I was beginning to wonder at what

point

I should raise the alarm for his non-return, especially as he had been

confident that he would return in time to sail to a more northerly

point on

the

island. He mentioned that he had signed a book, kept in a waterproof

metal box

at the top of each mountain, where climbers could record their success.

He had

been sorry that I had been unable to add my name, but from his

description of

the climb, I knew that I had made the right decision to stop where I

did.

I

had already packed most of the

gear, so we were able to get away by 1830. We beat our way

past the nearby

Nes. The

Wayfarer is tied up to a jetty just beyond the row of fishing sheds on

the

left.

of the naturally sheltered harbours we visited, and the whole area was well used, mostly by fishing vessels.  Even at 2330, there was still plenty of natural light to work by. In

Nes, we

were welcomed with a warmth that

I have experienced many times on sailing into a small harbour, where

seafaring

folk appreciate the seamanship required by small open-boat sailing, and

we were

told it

would be no problem to pitch our tents on a nearby grassy area. It was

Blunderbus is tied

up

to jetty on far side

of the water with Wilhelm’s red tent just visible against a shed on far

left.

...Above the moored fishing boat you can just see the crumbling peaks of the mountain on the small |

|

Day 4: Vega to

Hysvær

We

made a late start the next day, not setting

out until past 1500. A leisurely morning

stroll around the

immediate

area included a visit to the local shop to

replenish

our food stocks. Winds were very light when we set off, but Wilhelm was

determined

to maintain his sailing reputation with the local fishermen, and

patiently

tacked

his way out of the harbour entrance. We did, however, need to resort to

the motor

whilst weaving our way through the islands beyond, as these tended to

block what

little wind there was.

Once into more open water, we had an

easy sail to Hysvær, a group of over 50 small islands, a few of

which are

permanently inhabited. Wilhelm spotted a floating pontoon as we

approached one

of two islands with obvious signs of habitation. His

unusual (for me anyway) bigger boat

technique

always came to the fore whenever we approached any jetty: He

asked for the

fenders to

be put out. Every dinghy

sailor I

know always sails straight up to any landing place, and only sorts out

the

fenders and rope to tie up once berthed. I have to admit that

Wilhelm’s

approach was the more seamanlike though.

Hysvær.

All the gear

which has been unpacked from the front locker has been placed in a line

along

the edge of the jetty, with the hatch lid at the front, resting on the

first

item. Wilhelm was quite amazed at how much I was able to pack into this

space!

As

luck would have it, we happened

to land at a pontoon belonging to Øystestein Ludvigen who had

been the subject

of a Norwegian TV series entitled A

year in the Life, which showed the

variety of things he did to make a living on the island. These included

fishing,

keeping wild sheep, and collecting eider duck down. Wilhelm had already

explained to me how Øystestein had been very enterprising, using

his ingenuity

and many reclaimed materials to build a restaurant and a small heated

open-air

bathing pool.

Walking up over the brow of a hill along a short

grassy path, we came to his house where

Øystestein was on the roof with a high-pressure hose, cleaning

lichen off the

roof so that the rainwater collected could be used for drinking

purposes.

Wilhelm

talks to Snoøfridd on the

decking outside the newly built restaurant. Much of the platform was

made up

from pieces of timber washed up on the shores of the islands, some of the supporting sections being quite massive. Both Øystestein and his wife,

Snoøfridd, though seemingly always busy, were happy to entertain

Wilhelm and me

with stories of their life on the island. Whilst I was unable to

understand anything being said, I could immediately recognise the

energy of a

person who was obviously so at home in his environment. I looked around

the

very impressive restaurant he had built to cater to the various

visitors who now came to the island. Though it

was difficult

to see how regular visitors would arrive in any great number, as

there is no regular

ferry. Not that

catering for

any group was ever going to be easy, with no running fresh water or

mains

electricity. But Øystestein just seemed to look on any such

difficulties as

mere challenges to be overcome by one means or another.

Øystestein and Snoøfridd invited us

to share a simple meal with them, after which they

promised

to take us out in their 6-meter aluminium motor boat to show us the

natural

beauty

of the area. Øystestein finally stopped working at nearly 2200,

after

which we all retreated to the restaurant for a drink. The restaurant

had

apparently been open for the past three months. The

eating

area was indeed nicely finished and very tastefully fitted out in a sea

fishing

theme, with

nets draped from the wooden rafters. However, with no running water in

the

washrooms, and with the kitchen still being fitted out, it was just as

well

they didn’t have to satisfy any of the normal catering regulations –

not that any visitors would particularly concern themselves

with

such things. The hospitality and the excellent ‘home cooking’ on offer

could

not be surpassed.

Øystestein

and Wilhelm chatted for some time, and it was nearly

It

was 0100 before I finally climbed into bed that night, grateful that

Snoøfridd

had offered me a dormitory bunk to sleep in – which proved rather more

comfortable

than my camp bed on the boat!

... |

| Part 2 return to this log's index |