The Voice of Experience

Speaks

on the

Topic of

Self-Rescue

After a Capsize

by Uncle Al

Your Uncle Al has capsized

often

enough to

qualify as an expert in self-rescue. In fact, my wife,

Julia, and I

hold

a record that is unlikely to ever be broken: We

‘dumped’ in every one

of

the dozen or so events on the 1978 North American

Wayfarer calendar!

Prepare

for

the Worst!

Before we even start to talk

of

self-rescue,

it is essential to talk about the preparations that

every Wayfarer

owner

- racers and non-racers alike - must make!

Specifically, we owe it to

ourselves

and to those who might have to rescue us, to make

certain that our

Wayfarer

complies with Class Rule 34

- Buoyancy.

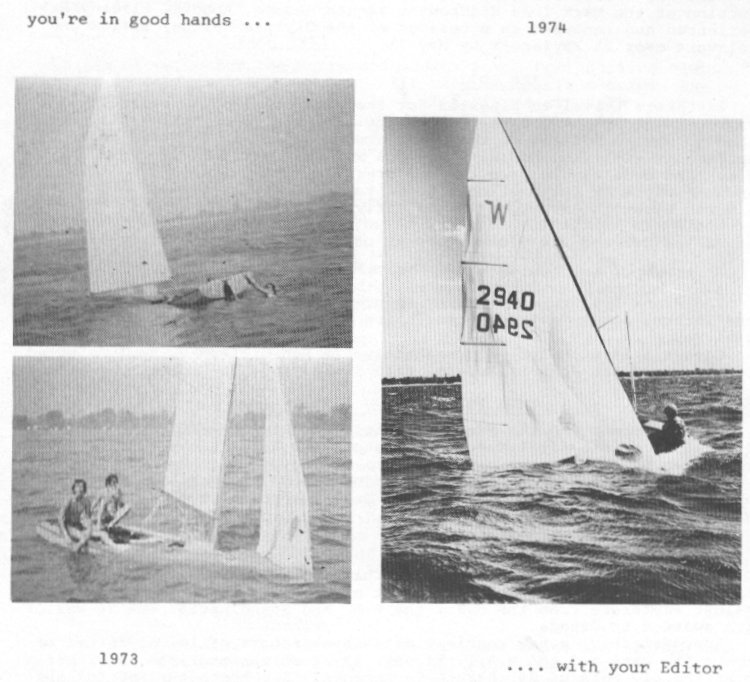

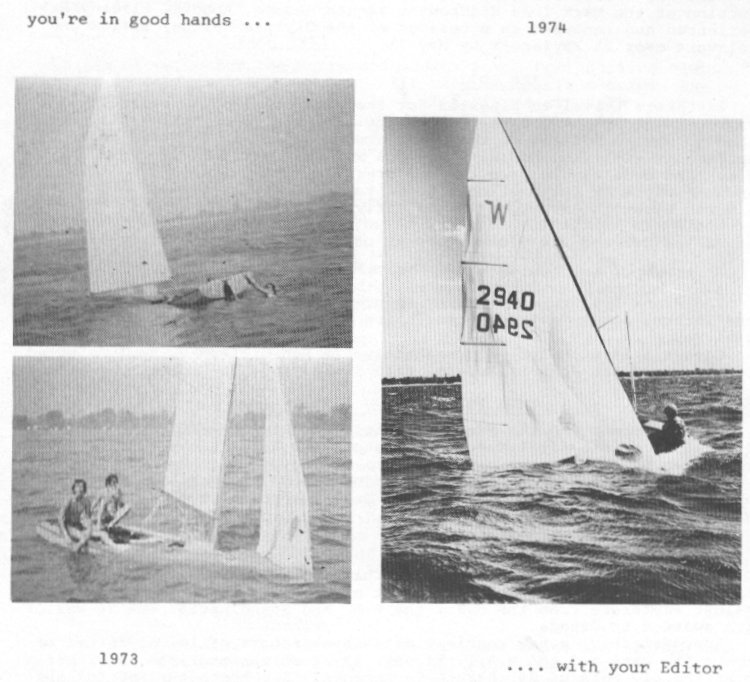

And you can still get into

trouble,

even

with perfect buoyancy, if you don't have your hatches

properly battened

down (below left, W852 in the 1973 North Americans

where a

lunch-time

beaching had left Al's centreboard stuck in the up

position and Al

capsized

the boat in a fit of rage and in a last-ditch

ill-advised attempt at

freeing

the board from below - of course the front hatch was

off since it was

such

a nice, not very windy day!), or make the

mistake of taking the

hatch

cover off to see why your bow is so low in the water

after the capsize

(below right, Uncle Al the 1974 North Americans!)

Needless to say, a proper PFD -

worn or

easily accessible - for each individual

aboard, and clothing appropriate to wind and water

temperature plus a

functional bailing bucket (tied to the boat!!!) are also

absolutely

essential.

Needless to say, a proper PFD -

worn or

easily accessible - for each individual

aboard, and clothing appropriate to wind and water

temperature plus a

functional bailing bucket (tied to the boat!!!) are also

absolutely

essential.

When

the

worst happens

Many of us live in fear of

capsizing on

a

windy day. One of the best ways to remove some of that

fear is to do

some

practice capsizes in a nice, controlled environment.

When I was a

Junior

Sailing instructor, we found that capsize practice was

one of the kids'

favourite activities, and of course, they soon lost

any fear of

capsizing

that they might have had.

But let us assume that you

have had no

capsize

experience. What is the worst that can happen?

Probably, it's a death

roll

where the boat capsizes to windward on a run and

immediately "turtles"

(inverts, goes mast down). With the mainsail all the

way out, sail and

mast can knife through the water very quickly, and in

theory, the hull

can come over right on top of you. I for one, was very

scared of such a

thing happening to me and of getting trapped under the

hull. But it has

been my experience (alas, too frequent!) that you

still end up beside

the

hull not under it, even after a death roll. Moreover,

the famous UK

cruiser,

Ralph Roberts, assures me that there is no problem

even if you do end

up

under the hull. There is lots of space between the

surface of the water

and the floor of the boat. In fact, Ralph pointed out

that in really

vicious

sea conditions, he has deliberately sought a bit of

shelter from the

waves

by going under the hull.

So we'll assume you have just

done a

death

roll and are now floating beside your turtled

Wayfarer. The good news

is,

that all the wild excitement tinged with fear is now

over. You can

relax

- unless, God forbid, your are sailing in

shark-infested waters. Check

that your partner is also OK, and think what a good

story this

adventure

will make. A bit of humour is always good - especially

if your crew

tends

to get a bit nervous.

I still remember one of my

first

death rolls.

We had driven most of the night to get to our Spring

Regatta on the

Chesapeake

Bay but awoke to the news that racing would be

cancelled for the

Saturday

due to small craft warnings for the Bay. Well, after

driving all that

way,

my crew and I decided to take W852 out for a little

run anyway.

Fortunately

both wind and water were warm for early May as we beat

north into

12-foot

waves. After a couple of miles, we decided we had

earned the right to a

nice ride downwind, and bore off to broad reach back

down to the

Podickory

Point YC. The first wave we caught seemed to carry us

forever on an

exhilarating

wild plane but as we started down the second wave, our

nicely balanced

helm became a non-existent helm. I looked back just in

time to see our

rudder blade porpoising about 30 feet astern. By this

time the boat had

borne away radically and the next thing I recall I was

floating beside

a turtled W852 with my crew, Freddie. There was not

another boat in

sight

anywhere, and the Bay looked awfully big as we climbed

onto the hull.

"Freddie!"

I said to my crew, "You missed a couple of spots here

when you cleaned

the bottom of the boat!!!" That gave us both something

to smile at and

then we sat for a while and planned our course of

action before we went

about the job of trying to rescue ourselves. We were

certainly glad we

had the prescribed bailing bucket, but without a

rudder, things were

challenging.

We ended up working our way downwind towards the PDYC

- under jib

alone,

I believe, and steering with a paddle, and someone

came out in a motor

boat to tow us the final 100 yards before the outgoing

tide could sweep

us past the harbour mouth.

Recovering

from capsize

As far as I'm aware, the

approved

procedure

taught in most sailing schools in Canada is that one

of the crew should

swim forward and hold the bow head to wind. With all

due respect, I

can't

see how that helps. In fact, the last thing I want to

be doing with a

boat

full of water is pointing straight into a 20-knot

wind. By the time

I've

stopped going backwards, I'm sure I'll capsize again -

not to mention

having

sapped my crew's strength.

In my (extensive) experience,

the

ideal position

for a boat you want to right, is sideways to the wind.

However, you do

want to make certain that you

never

right the boat with the mast and mainsail pointing

towards the wind!

I did that once in a

Fireball and of

course the wind got under the main and flipped the

entire hull and mess

of tangled ropes right over on top of me. That was the

closest I've

ever

come to panic as I struggled to get untangled before

the hull trapped

me.

Al's

note 2 Dec 09: Thanks to Chris Codling whose 2009

International Rally

pics included this series of pics that shows "what

you should not do",

as Papa Bear once said in

the Berenstain Bears' The Bike Lesson

- the very thing I've been on the look-out for:

The tow boat is not helping any by turning away from

shore and towards

the camera. A 90° turn to port will leave this mast

pointing more

or less into the wind, where the crew working to

right the boat will

likely discover that righting is easier with the

main reefed. And once

the head of the main comes clear of the water the

righting process

becomes all too easy as ...

... the stiff breeze fills the sail, whips it to the

lee side (head

down, crew!!) with a 99% chance of ...

... another

capsize - even with this reefed main - imagine how

much more certain a

full main would make the second capsize!! Noble

effort by the crew but

doomed to failure, I expect. The good news is that

now the mast will be

pointing downwind for the second try at re-righting. ... another

capsize - even with this reefed main - imagine how

much more certain a

full main would make the second capsize!! Noble

effort by the crew but

doomed to failure, I expect. The good news is that

now the mast will be

pointing downwind for the second try at re-righting.

In

defence of the rescue team!!

-----

Original Message -----

From:

Ralph Roberts

Sent:

Thursday, December 03, 2009 4:39 AM

Subject: capsize pics

Hi Al,

Glad you found the pics

ideal

for your guide to capsizing! Obviously they do

illustrate your points

well, and I wouldn't suggest there is any need to

amend your

statements, but in defence of the (brilliant!) French

instructors, the

situation occurred near the mouth of a tidal river in

Brittany, and the

current needed to be experienced to be believed. The

guy on the rescue

craft therefore had to hold the boat against the

current, rather than

the wind direction being any priority. As can be seen

in the photos,

the back tank is at least partially flooded (not

surprisng with the

inverted boat being pinned against a fish farm by the

flood tide for 20

to 30 mins), so the transom of the boat is beneath the

water when

righted, making it incredibly unstable. In fact, I

thought the only

chance of saving the boat would be to tow it in its

inverted state to

the shore - obviously sacrificing the mast, but at

least saving the

boat. The fact that the instructor did somehow manage

to get it to

shore in an upright position was down to his great

skill. (I didn't see

the latter stages, as I took the Dutch crew back to

our base for a hot

shower and change into dry clothes)...

Best wishes, Ralph

The good news is, however,

that a

capsized

or turtled boat most often seems to end up lying

sideways on to the

wind

direction with the mast pointing where you want it -

downwind!

In any case, recovering

from

a

"Greenlander"

(as the Danes call it when the

mast

points

down at the bottom of the sea), is a

three-stage

operation (if

your

mast is already horizontal, skip step A)

A.

to move

the mast

from vertical (pointing at the sea bed) to

horizontal

1. If

necessary

and

possible, uncleat main and jib sheets so that you

will not have to drag

your main and jib through the water like giant

paddles.

2. If

necessary

and

possible, put the centreboard into its full down

position.

3. One

crew now

stands

(as best he can!) on the windward

rubrail, grabs the tip of the board and tries to

hang his butt as far

out

to as possible in order to start the mast back to a

horizontal

position.

Depending on the situation and crew weight, it may

require both crews

hanging

off the centreboard tip to get the job done,

especially if main and jib

sheet are not freed. And of course, if your mast is

stuck in mud, you

will

most likely require outside assistance.

4. If,

for any

reason,

the centreboard cannot be used for the above

purpose, use the jib sheet

instead of the centreboard. I've done this, and it

works! Grab the jib

sheet on the leeward side, lead it over the hull

towards the windward

side

and then hang off it while standing on the windward

rubrail. And if you

can't find a jib sheet, tie any piece of line

available, around the

leeward

shroud at deck level and use it the way you would

use the jib sheet. (I

have not tried this but it makes sense, I

think/hope?)

B.

righting

the boat

from the mast horizontal position

The

standard way

to

accomplish this by having one or both crew members

stand on the

centreboard.

The further out you move from the hull, the more

leverage you will

exert.

The routine should be as follows:

1. Boat

position:

Make sure that your

mast is

pointing straight

downwind or at least no more than about 45º to

either side of

straight

downwind. This is one time when it's worth swimming

the bow around

until

the mast points in the right direction!!

2. Sail

preparation:

If necessary and possible, lower the spinnaker

(if it

was

flying),

and uncleat main and jib sheets so that you will not

have to lift a ton

of water as well as the sails.

3. Getting

the

leverage: Put the centreboard into its full

down position.

4. Using

the

leverage: One crew now stands on the

centreboard, grabs the edge

of the

deck

and tries to hang his butt as far out to as possible

in order to start

the mast back to a vertical position. Depending on

the situation and

crew

weight, it may require both crews on the centreboard

to get the job

done,

especially if main and jib sheet are not completely

freed. Except under

exceptional circumstances - which I cannot at this

time imagine - do

not lower any of your sails except a

spinnaker

that may have been up. The main and jib have an

excellent dampening

effect

on the speed of bringing the boat back upright at a

reasonable speed

and

even more importantly, they make the boat far less

prone to

inverting/turtling/doing

a Greenlander! And besides, you'll need those sails

to complete your

self-rescue!!!

5. Getting

one

person

back into the boat: With practice, you will be

able to judge the

moment

of no return and flip yourself back into the boat as

she rights -

rather

than waiting for the mast to get totally vertical

and then trying to

climb

back into the boat (which is not always easy -

especially if you're

wearing

bulky clothes and PFD). Only one person should do

this. The other

should

hang onto the hull and relax for a moment.

An

impressive

method

that I've seen a 5-0-5 use, is having the heavier

person stand on the

lowered

board while the lighter person remains "inside" the

cockpit. The boat

is

then righted with one person already in it and ready

to do the

necessary

to keep the boat under control and not let it

capsize again.

C.

Completing the

Recovery

1. Uncle

Al's Special Trick!!! The very first

thing

you should do after getting one person back into the

boat, is to fully

raise the centreboard.

Wayfarer

Man and

I

learned this the hard way in the '92 Worlds at

Hayling Island. In

(warm!)

winds of Force 6-7, we were one of 28 of 52 boats to

dump. Having

thoroughly

washed MOJO (kindly lent to us by Phil

Warner!), we righted her

with no problem in the two-metre chop, but the first

gust put her over

once more as she "tripped" over the fully lowered

centreboard. We

re-righted MOJO

a second time, let the sails totally luff and this

time, raised the

board

completely.

With the

board

up, no

forward

momentum, and sails

totally luffing, the

boat will stabilize

sideways

on to the wind, even when filled with water - i.e.

you don't need to

touch

the tiller, and heel is no particular problem!!! You

can just sit and

relax,

so I've taken to calling this R & R mode (Rest

& Relaxation).

2. Retrieving

the

crew:

The beauty of going into the R & R mode (board

up, no forward momentum, and sails totally luffing)

is that you are now free to concentrate on

essentials such as helping

your

crew get back into the boat. You can help him or her

a lot by simply

heeling

the boat to windward (until the windward gunwale is

under water, if

necessary!!)

to enable your crew to crawl/slide over the gunwale

and back into the

boat.

While such heeling would be suicide if you had any

forward momentum, it

is perfectly safe when the boat is dead in the water

- if you'll pardon

the expression!

3. Clean-Up:

Now that you are both safely back aboard, is a good

time to do a bit of

cleaning up. For starters, grab any gear that is in

danger of floating

away such as paddles, floor boards or half empty

cognac bottles, and

store

them as best you can - if all else fails, one of you

can hold onto

these

while

the other bails!

4. Bailing:

Of

course, your bailing bucket was tied to the boat,

right? We (often) tie

ours to a halyard. Another of the bonuses of the R

& R mode is that

the fully raised centreboard keeps the water from

gushing into the boat

through the centreboard box faster than you can

bail. You'll still take

water over the side occasionally but we found that

even in the nasty

Hayling

chop, we were fairly easily able to bail MOJO

to the point

where

the water was barely above the floorboards and we

could sail again. You

may as well close your automatic bailers, before you

start using the

bucket.

The R & R mode is also good for letting you take

the time to remove

in relative calm, any ropes that have partially

escaped through the

bailers.

Closing the bailers will also make sure that no

ropes get stuck in them

- something that always seems to happen if you leave

the bailers open

after

you capsize.

5. Getting

underway

once

more: Once you have lowered the water level in

the boat to

near

the floorboard level, it is pretty safe to stop

bailing and start

sailing.

But first, remember to

- stow

any

loose gear that

may get in your way and ropes that may want to go

out through your

bailers

with the water

- grab

some

refreshment before

the real action starts again

- put

the

board

half down,

open the bailers and move your crew weight well

aft

- sail

a

reach

for best bailing

speed

Note:

I

have seen

Wayfarers capsized, righted, and sailed dry without

the benefit of

bucket

bailing - once even with the spinnaker up in a

"kuling" (30 knots +) on

Furesøen near Copenhagen. One of these days, I must

try that.

Although

I've never managed this myself, it is clear that you

must put your crew

weight as far aft as is possible. If you do it right,

I suspect you

should

be able to slop a lot of your in-boat water out the

back of the boat

over

the transom - even at speeds that would not be enough

to make your

bailers

work - provided that your weight aft has almost

submerged the transom.

The other benefit of weight aft once the boat starts

moving is that the

pointy section of the bow (which will easily deflect

your course and

overpower

your rudder when the boat is full of water and/or

going fast), will be

out of the water and you'll be sailing on the flatter,

more forgiving

aft

sections of the hull. I'd be happy to hear from anyone

who would care

to

share the experience they've gained using this method.

Best wishes for a safe and

happy

2001 from

Uncle

Al (W3854)

|

... another

capsize - even with this reefed main - imagine how

much more certain a

full main would make the second capsize!! Noble

effort by the crew but

doomed to failure, I expect. The good news is that

now the mast will be

pointing downwind for the second try at re-righting.

... another

capsize - even with this reefed main - imagine how

much more certain a

full main would make the second capsize!! Noble

effort by the crew but

doomed to failure, I expect. The good news is that

now the mast will be

pointing downwind for the second try at re-righting.