|

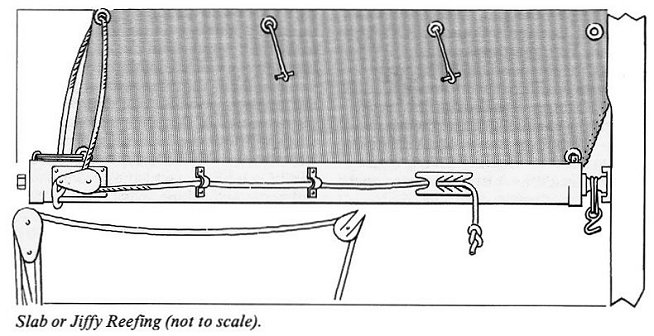

Rigging and Sails THE stresses on the rigging when cruising are usually less than when racing. The wear, though, during a long cruise, is much greater, and so is the tendency of fastenings to work loose. Turnbuckles should be tightened and wired, or replaced with lanyards, or perhaps bypassed with a lanyard, in case of failure of the tumbuckle screw. Shrouds and forestay must be examined and if any single wire is broken or badly kinked, the shroud should be replaced. One Wayfarer sailor doubles his shrouds for ocean cruising. All screws, bolts, rivets, tangs etc. on the mast must be checked, and replaced or repaired if damaged. Cotter pins should be taped. Your masthead pennant will be up there for the duration of the cruise, so make sure it will not work loose. Check the bow fitting and make sure it is secure. Look at the chain plates and their fastenings to the hull or knees. Weaknesses in the attachments of the standing rigging may be very difficult to correct, and that may be the designer's or the builder's fault, but the safety of boat and crew is the sole responsibility of the skipper. In the event of failure of a fitting, and a consequent disaster, it is not of the slightest value to be able to blame someone else. So weaknesses have to be corrected before you start. Check spreaders and spreader fittings; tape their outer ends and anyplace where the sail is going to chafe. Spreaders are important for the security of the mast and if one comes adrift, sail must be shortened immediately to reduce lateral stresses. Look closely at the mast step, pivot, and tabernacle, and strengthen if necessary. Also examine the rudder and centreboard for cracks, and make sure their fastenings, pivot bolt, and pintles are secure. If you anticipate lowering the mast while on the water, it may be worth splicing a rope tail to the forestay and leading it through a block or smooth shackle back to a stout cleat behind the wave breaker that you can reach from the cockpit. Then you can lower the mast without going on the foredeck, provided that the lowest two piston hanks of the jib are not attached (they will foul the rope-tail splice). Incidentally, and this is a heavy weather problem, if you have to take the jib down and sail under main alone, make sure you tack down the jib halyard to the bow fitting so that you have, in effect, a double forestay. It may prevent a broken mast! For halyards we prefer rope to wire, because wire can wear the sheave, and can jump off it and jam. The rope should be durable yet keep stretch to a minimum. We take a spare length of line long enough for a main halyard. We also carry and reeve the spinnaker halyard, even though we do not usually carry a spinnaker when cruising. The spinnaker halyard can stand in for a jib halyard or replace a broken shroud, provided one uses reduced sail. It is also handy for hauling up the laundry. Sails. During most of the cruise, there will be either enough wind or too little, and for both cases you will want your full racing sails. The dinghy will be more heavily laden, and it would be a mistake to go off with small sails just because you are cruising. Mainsail. A cruising mainsail can be simplified by dispensing with battens. The only purpose of battens is to prevent leach flutter in a sail cut with a large roach and the only purpose of the roach is that extra tenth of a knot when racing. You lose very little speed by cutting off" about two-thirds of the roach, and dispensing with battens. Leave a little roach, or you get a light leach. A sail-maker would do this for you, but on our Wayfarer mainsail, we did it ourselves and came out with a sail that sets well. We appreciate being able to drop the sail into the boat and not worry about treading on the battens. It also makes reefing easier, and simplifies rolling the sail around the boom for the night. Reefing. The ability to reef is essential, not optional, for open water cruising. If racing gear or fittings prevent it, they must be removed. You have got to be able to reef on the water in a blow and you may not have a great deal of sea room. Thus it is important to be able to do it promptly and without too much drifting. Most

people find that jiffy or slab

reefing

is quicker and easier than roller reefing. (A significant disadvantage

of roller reeling is the torque on the gooseneck when sailing hard

while

reefed. I have twice broken the gooseneck this way.) We installed

reefing

cringles ourselves with a kit. Or you may like to get a sailmaker to do

it. The illustration shows the fittings and their relative

positions.

...   before reefing… The

first reef should reduce the

mainsail

area by about thirty percent. The leech and the luff cringles take

practically

all the strain and the intermediate reef points can be quite thin line

or shock cord with only singly reinforced grommets. The points merely

keep

the bunt of the sail from flapping. The luff reefing cringle can be

secured

with a hook permanently attached to the gooseneck.

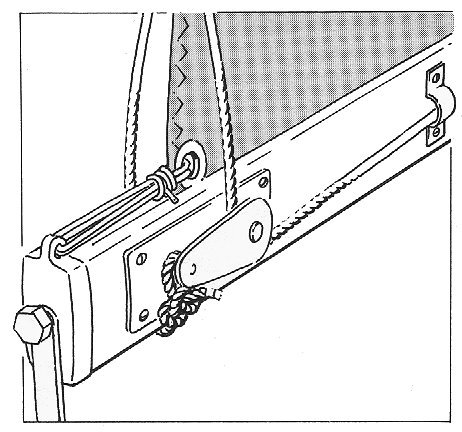

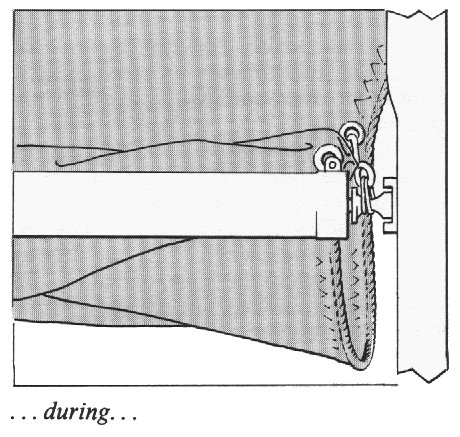

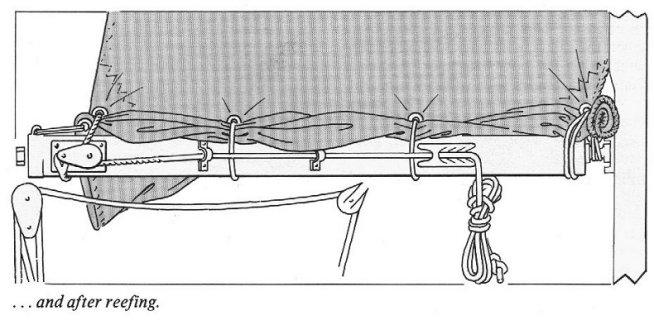

...  Jiffy

reefing can be performed in about

thirty

seconds without change of direction or loss of speed. Tidying the

canvas

from the tack aft takes a little longer, depending on the

circumstances.

The slack canvas at the tack should be secured with a lashing through

the

luff cringle. The clew, unless you heave-to, is, of course impossible

to

secure and we usually leave it, providing it is not fouling the

mainsheet.

The result looks untidy but is extremely effective.

...

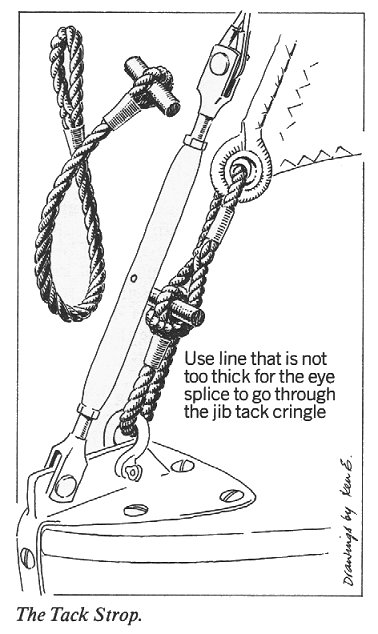

To un-jiffy reef takes more time and may require rounding up into the wind to hoist sail again. (A further advantage in this rig is that the main may be partially scandalised in calm weather, to give headroom to a rower.) If you are on a long open water cruise and unable to reach shelter before a real blow arrives, it is well to be equipped to pull in a second reef, or else to continue with roller reefing on top of the first slab reef. Our second reef reduces the mainsail to forty percent of its original area. Sailhead flotation or masthead flotation is recommended to prevent turning turtle if capsized. Enough styrofoam (or cellular plastic sheet) sufficient to displace 10 lb. of water (e.g. a triangle of two to three square feet, one and a half inches thick) in a pocket at the sailhead should suffice. Several thin sheets of foam are more flexible than a single thick slab. Be sure the foam is "closed cell" and not a sponge! Foresails. The regular racing foresail or genoa is fine for cruising. The plastic window is amazingly robust - ours is over 15 years old, and has not cracked or worn through its stitching. When sailing with a reefed main, the genoa may be too much foresail, and taking it down altogether leaves the boat unbalanced with a heavy weather helm and too much strain on the rudder, tiller and helmsman. A genoa can be reefed at the foot, with luff and leach cringles and one or two reef points. Alternatively, a working jib about half the area of the genoa is a useful sail to carry. It is

important to make things easy

for the

crew shortening sail on the foredeck, as he will be doing this when the

wind gets up and there may be quite a sea running. Replace the tack

shackle

with a strop that fixes with a toggle and eye as shown in the

illustration.

It is

very easy to release and to fix

when

the tension is off the halyard, and has no shackle or pin to drop in

the

water. If you want to make the strop, the toggle can be secured by

whipping,

very tightly indeed; and an eye can be made the same way. Splicing both

is better and is good practice. We use a longer strop for the working

jib

than for the genoa, and each sail's strop is left through the tack

cringle

and stays there when the sail is in its bag. A sturdy snap shackle on

the

bow fixture or jib tack is faster, but tangles with other equipment.

We prefer piston hanks to the plastic ones which are used for racing. They do need to be kept oiled and in good condition. Spinnaker. Some people like to cruise with the spinnaker and try to plan for long down-wind passages. We find we so rarely get an opportunity to use it that it is not worth the space it occupies, and we do not carry one. For downwind passages in strong wind and with a sea running, the safest and most comfortable way is to lower the main and wing out two jibs on poles. This greatly reduces the risk of broaching, but you cannot stop quickly. Don't fall overboard without a life-line attached. Trysail. The working jib doubles as storm trysail if the following adapter is made to run up the mast track: a narrow strip of canvas, the length of the luff of the jib, with a bolt rope sewn in along one edge to suit the groove in the mast, and along the other edge eyelets to suit the jib's piston hanks. The boom is not used. Fairleads for the sheets are necessary and the spinnaker sheet fairleads may serve. This "try-sail adapter" idea is from an English sailor named Peter Clutterbuck. I do not know how often he has used it himself. In conditions that warranted a storm trysail, I would probably be lying to a sea anchor with the mast down, or lying on a beach in a sheltered cove if I had listened to the weather forecast. Light

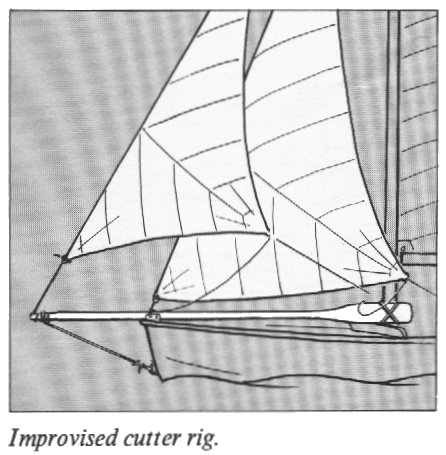

Air Sailing. More often than a

storm,

you will have to contend with light airs. If you are carrying a working

jib, you might as well use it in addition to the genoa. It can be

rigged

out forward on a paddle or oar, or it may be worthwhile to make a

bowsprit

that lies along the foredeck. On the Wayfarer, the inboard end of the

bowsprit

is wedged under the wavebreaker and a bobstay runs to the bow ring at

the

stem. The working jib is set as a flying jib, using the spinnaker

halyard.

This arrangement is complicated to tack and it seems to add very little

speed when hard on the wind. It does help noticeably on a reach, if you

are not up to hull speed.

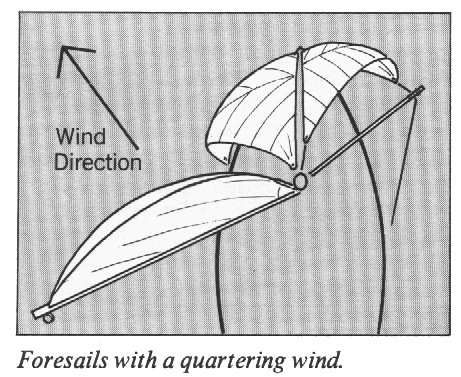

With

a quartering wind, you can try a

main

and two foresails, with the smaller guyed to windward on the whisker

pole

with a downhaul.

...

Auxiliary Motive Power. We do not carry a motor; nor have we cruised with anyone who does. Oars and paddles are more reliable, cleaner, lighter, less expensive, less magnetic and do not require potentially explosive fuel. If you have to travel up a river you might think it worthwhile taking a motor, otherwise I recommend oars. Rowing five miles, without hurry, in ten to twenty minute shifts is not hard work. We can make about two knots but one and a half is sufficient and easier. You can sing "The Volga Boatman" or "The Skye Boat Song" if you like. There is no call to hurry cruising but there is reason to think ahead. That is, to realize in good time that you will need to start rowing if you want to be in before dark. It is essential to wear gloves for a row of more than a few minutes, unless your hands are already used to it. Leather sailing gloves without fingers are excellent. Any leather or work gloves that will stand up to the wet will do well. |