|

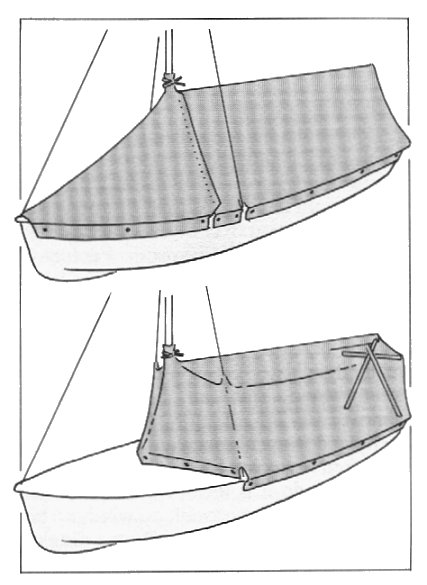

Camping You can sleep ashore in a small tent, or in the boat under a "boom tent" which will be described below. Generally, it is better to plan to sleep on the boat unless you know there will be somewhere ashore to camp. In the areas you do not know, and in uninhabited areas, sleeping on the boat is usually advisable, but there is no harm in taking along a small land tent as well. Many areas of the Great Lakes are too rocky to drive in tent pegs, and you will need to tie guy ropes to trees or weight them down with rocks. (Al's note: Free-standing tents, which are practically the norm these days, are a good solution.) An advantage of sleeping on the boat is that your stores and equipment, and the boat itself, are there with you and you are better placed to protect them from damage by wind, sea, marauding animals or humans. We usually sleep afloat, either swinging at anchor or tied to trees with a stern anchor to hold the boat off. Pulling the boat up a sand beach is an alternative, but be sure the hull is well supported along its length and not perched on a rock. Boom

Tent. The illustrations

show two

different types of tent design suitable for a dinghy. The first is a

simple

ridge tent which can be slung over a crutch-supported boom. Fastenings

around the mast and shrouds need to be tight to keep out the rain. The

skirt of the tent can be secured beneath the rubbing strake with

velcro,

press studs or hooks. As additional security for extreme conditions,

tangs

or grommets may be sewn into the tent so that lines can be passed under

the boat to hold the tent down in two or three places.

The

tent may be designed to come right

to

the bow of the dinghy, or just forward of the mast. The longer bow

gives

good storage space protected from rain, but has the disadvantage of

making

the dinghy swing more at anchor in a wind. The second tent (supported

by

the shrouds and a spreader on the boom crutch) allows sitting room at

the

sides whereas in the first, you can sit only amidships.

Most dinghy tents are made of canvas, which is durable and relatively easy to repair, but is heavy and shrinks if stored when damp, and grows mildew if damp for a long period. There is frequently heavy dew on a summer night and unless you are willing to delay your start far into the morning, it is usually impossible to dry the tent before stowing it. We

are experimenting with ripstop

nylon, which

is lighter and takes less stowage space. It should be less subject to

shrinking

and less affected by mildew. (Al's note: An excellent source of

advice

here would be our resident expert cover and boom tent maker, Hans

Gottschling

at hansg@gottschlingboatcovers.com)

It

may be possible to design your tent so that oars are used as struts or

side battens. (It is almost a principle of dinghy cruising that every

piece

of gear should have more than one use.) Entrance to the tent may be

over

the bows, at the shroud, or at the transom. Factors to consider are

configuration

of your boat, and whether you can safely stand on the bow when afloat.

Choice

of Camping Spot. The

first and

really the only essential in camping is sheltered water. You can

compromise

on almost every other factor. A great deal can be judged from a large

scale

chart.

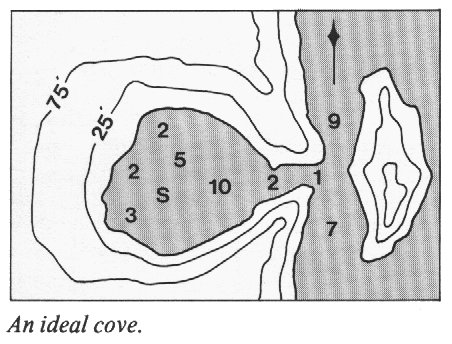

You

do not often see a cove like the

above

but if you do, it is ideal. Nothing else can get in: no waves, no

swell,

no wind, no big sailboats, no powerboats. Only a dinghy! The cove has a

sandy bottom and probably a sandy beach.

...

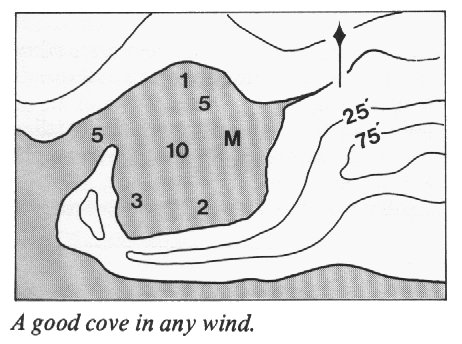

The

cove in the drawing above is also

good,

as any waves that come in through the narrow entrance will dissipate in

the wide basin and on the shelving beach, and there is a hook to lie

behind

if the wind comes in at the opening.

...

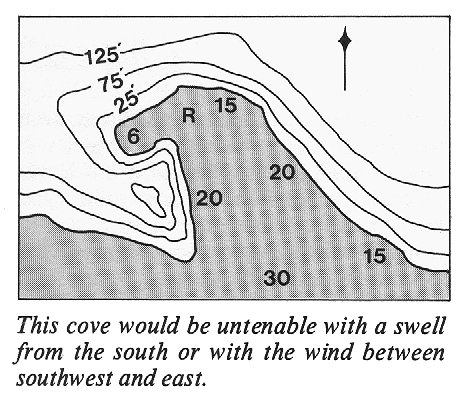

The

cove shown above is likely to be

terrible

if waves or swell are from the SW to E, as they will increase in

amplitude

in the funnel-shaped entrance to the cove, and reflect off the steep-to

N shore into the one spot that looks to be sheltered.

If you cannot find a well protected cove, look for a beach that you have to approach up-wind, i.e. a "weather shore". This can be acceptable if the weather is settled with no threat of windshift. Often there are purely local windshifts after dusk and in the late morning - the land and sea breezes - but these will not usually get up much wave action. Beware of any shore on to which a swell is coming from the open lake. Listen to a weather forecast before you pick your camping site in the afternoon, and form some idea of what windshifts can be expected. If, for example, SW winds are forecast, and you are enjoying a north or east wind that the weather bureau does not seem to know about, what you are experiencing is probably a local sea-breeze caused by convection over hot land, and the SW wind will come in after nightfall. Look for protection by shoreline, islands, or a shallow bar, trees as a windbreak, or a sandy beach or at least some shingle or fore-shore free of trees so that you have somewhere to cook. Reeds are excellent protection from waves, but often the shore behind them is marshy. Avoid cottages, Indian reservations, sewage outflow (beware of creeks in inhabited areas), rocks and boulders just below the surface, grazing cattle, poison ivy. An island is often more peaceful than the mainland. Think of the need for toilet. In an uninhabited area it is permissible to use the outdoors but bury everything with a trowel, or a few small rocks. This is legal and does not upset the ecology. Beaching. You may have been out all day in the wildest weather, but the biggest risk of damaging your boat occurs when you are coming in to land. Avoid coming in to a lee shore, that is, with the wind blowing onshore, except in light airs, or to a sandy beach that you know is free of rocks. In any case, come in very slowly with the mainsail ready to drop and the jib ready to fly. Beating up to a weather shore is much safer and it does not matter if you have to row or paddle the last few yards. Judge when you are something less than 100 feet off the beach and drop an anchor from the stern. Pay out the anchor rode and use it to stop as your bow nears the beach. The rode can then be secured to a cleat near the transom, to the traveller rail if this is robust, or by a hitch around a stout stick wedged across the transom cutout. (The bitter end of the rode, of course, must be tied to the centre thwart or to something solid that it can't slip off, before you let go the anchor.) Then

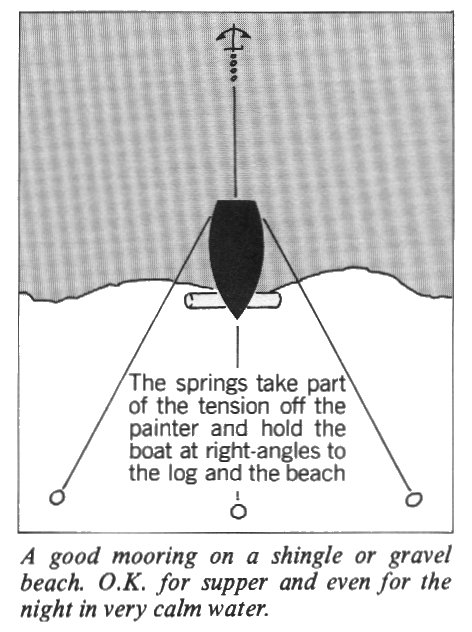

take a bow line ashore,

carrying a spare

length to bend on, if the nearest tree, heavy log or large rock is too

far for the painter to reach. When there is even the slightest swell

coming

in, or a cross wind, you will need spring lines from the quarters to

run

ashore and perhaps an extra line from one or both sides of the

bow. ..

Unless

the beach is soft sand, and free

of

rocks, it is essential to prevent your boat from working on the bottom.

Safe mooring should be the skipper's concern while the crew is getting

out the stove or lighting a fire to make coffee. The bow of the boat

can

often be lifted on to a piece of driftwood. Look under the boat for

rocks

sticking out of an otherwise smooth bottom.

When beached, or anchored close to a rocky shore, remember the possibility of an occasional large wave, or the wake from a nearby power boat or a distant freighter, surging your boat towards the beach or bumping her on the bottom. If you cannot be sure the boat is safe as beached, then pull off by means of the anchor already set astern, into a foot or two of water, and accept the fact that you are going to have wet legs wading to and from the boat. If the beach is sand, mud or fine shingle and if you have one or preferably two boat rollers, you can drag the boat up the beach. (Al's note: One thing you never want to do is beach your boat such that the centreboard is directly above waves breaking onto sand. The sand can get washed up between the box and the board and make the board impossible to pivot!!) A tackle secured to a tree or to a well-set anchor can help with this. Your main sheet tackle is probably not strong enough, but the boom vang tackle may be. If you are forced to camp where there is an onshore wind, and if the beach is suitable, consider rolling the boat up stern first so that waves coming in hit the bow and not the stern. They are less likely to lift the bow or to break into the boat. Anchoring. In a sheltered spot, the boat can probably ride safely with the bow beached during supper, but for the night it is often best to pull off into a few feet of water. Mosquitoes are quite often less troublesome if you anchor some distance off-shore than if you are very close in. If you are going to swing at anchor, then it is necessary to check that you will not hit anything, whatever wind-shifts may occur. It may be well to set two anchors with a "Bahamian moor" (two anchors over the bow set parallel to the stream) or whatever system you fancy, so that if the wind shifts, your rode does not foul the anchors and cause them to drag. The large number of articles on anchoring in yachting magazines shows that many people have problems with it. So do we. One thing you can often do in the shallow water a dinghy anchors in, is to swim down to the anchor and make sure it is well set, or even pile rocks on it You can also climb down the anchor rode to free it. Beware of anchoring among rocks or dead-heads in water too deep for you to get to the bottom; you have not got much leverage or power on a dinghy to help you bring up a fouled anchor. In a dinghy, it is difficult to gain sufficient sternway to set the anchor, if you have dropped it in the usual manner head to wind. Try sailing it in, by letting it go over the stern while you are sailing down wind. When enough scope is out, snub it to a cleat near the stern (or take a turn around the thwart with a bight of the rode). The rode should already have been led through the bow chock and round to the stern on the side opposite to the boom, "outside everything". Once the rode is snubbed and the anchor is set, clear it from the stern cleat (or take the bight off the thwart) and let the bow chock take the strain, which will swing the boat head to wind and allow you to take the sails down. When

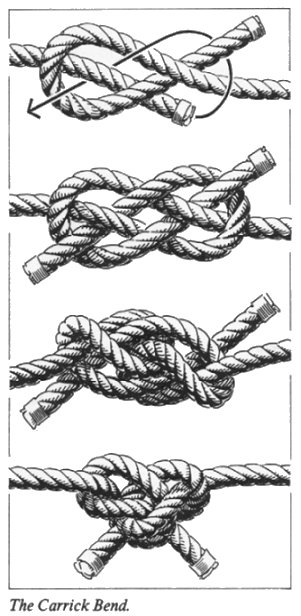

anchored, if you take lines to

the shore

and the boat is not free to point head to wind, strain on the moorings

and anchor is considerably increased in a cross-wind. This type of

mooring

needs long lengths of line and you may need to join two or more. Join

them

with a carrick bend, or an anchor bowline tied into an eye splice or

into

another bowline. The carrick bend is less subject to wear and weakens

the

rope less.

A

reef knot is unsafe, and I would not

trust

a sheet bend unless I could be sure it would be continuously in

tension.

I have never known a carrick bend, once pulled good and tight, to have

come undone accidentally. Also it is never jammed in the morning even

if

it has been wet all night. Carry plenty of long lines suitable for

mooring.

Except where subject to chafing, quarter inch synthetic line is strong

enough. Don't forget to unship the rudder and raise the centreboard.

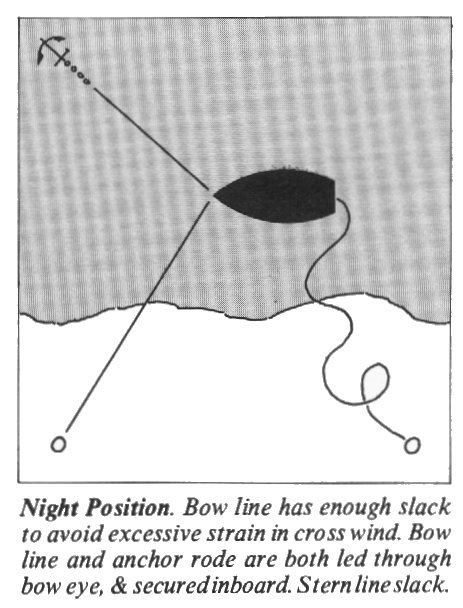

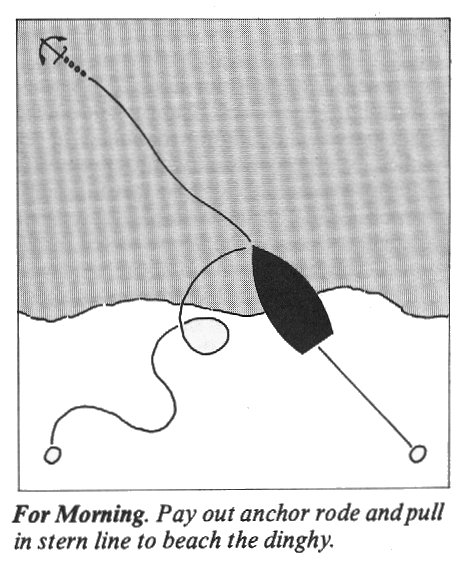

Night time. We usually use sleeping bags on air mattresses, one each side of the centreboard trunk. The weather is often too hot when you go to bed, but in the cooler small hours of the morning it is good to have sweater and socks within easy reach. Always have your shoes at hand, rubber boots, foul weather gear, and a flashlight. A thunderstorm on a summer night can pack winds that would shake almost any mooring. Also know where your paddle is, as anchors have been known to drag. A small thing to remember is a shock cord from a shroud round the halyards to keep them from slapping against the mast. If a stormy night is expected it is well worth while making a thermos of hot drink before you turn in. We usually sleep with the tent window open, protected with its nylon mosquito net, and we leave a mosquito coil burning at the stern and any place where the little devils can get in. These coils seem to smoulder away very safely as long as they are on a piece of foil to catch the hot ash. Sprays or skin mosquito repellent are alternatives but be sure that the sprays will not damage your tent or equipment, and that repellent on your skin is not going to harm your eyes if it gets rubbed in during the night. Items left ashore overnight can get wet or blown away. Animals can get at food or do damage searching for it among gear that has the smell of food about it. In some areas one must be aware of the possibility of theft or vandalism. A basic rule is not to leave anything ashore which you could not afford to lose. This means that there is not much that you can leave ashore. Before

it gets dark, check your

moorings carefully.

When you expect a blow, double the lines that will take the strain.

Think

which way your boat will move if the wind shifts, and be sure there is

no way it can bump a rock. Even if you are up and out of your sleeping

bag before damage is done, it is, at best, unpleasant and difficult to

alter your moorings in the middle of the night. ...

The

dinghy is thus free to swing head

to

wind, but cannot float over the anchor to foul it, nor pull it out

backwards

after a major windshift. All three lines should be of a material that

sinks,

or have a small weight attached a few feet from the boat, so that she

can

ride over them.

...

Legal Aspects. There is a popular belief that no one in Canada can own the foreshore, and, therefore, that you are not trespassing by landing on a beach. I have checked with a lawyer, and found this is not necessarily true, either on the Great Lakes or elsewhere. In some places the government owns the beaches, in others, the Township. Sometimes the owners of the properties fronting the lake were offered title to the foreshore. Some took it up but others did not. So the fact is, you cannot tell, and, quite apart from the unpleasantness, it is useless to get into an argument with the owner of the land behind the beach. If you are a "distressed mariner" and have to land on someone's beach, you theoretically have a right to stay for 24 hours if you need to. This has not been tested in Ontario courts, but it might be worth knowing about if the occasion should arise. |